People rarely reflect on the fact that the clothes they wear, the cars they drive, and the other goods they consume come from all over the world or are assembled from parts that came from all over. In principle, a country could produce everything it needed. An economy that is entirely self-sufficient and therefore imports nothing is called an autarky. But while economic self-sufficiency may sound attractive in principle, in practice it hampers economic growth. The countries that strive for autarky (none fully achieve it) tend to be the ones where autarky is part of an authoritarian regime’s ideology. North Korea, for example.

The countries that prosper are mostly those that embrace international trade. Just as Alicia and Boris enjoyed gains from trade in the chapter on Production Possibilities and Gains from Trade, so two countries can enjoy gains by trading with one another, each concentrating on the production category where it enjoys a comparative advantage. For example, a country with a lot of flat prairies can grow food crops for sale to a country with a colder climate and mountainous terrain, while the mountainous country may grow trees that can be harvested for lumber to sell to the flat country.

All that said, international trade is not without its challenges. In this chapter, we look at two issues: protectionism and trade deficits.

Protectionism

Suppose that a country named Cornucopia has a comparative advantage in producing food crops, while a country named Treedonia has a comparative advantage in producing lumber. If Cornucopia starts exporting crops to Treedonia, while Treedonia exports lumber to Cornucopia, then both countries benefit from the arrangement. Each can consume both more food and more lumber than before. However, individual industries in each country are harmed. Specifically, the new arrangement is bad for Treedonia’s farmers, because in trying to sell crops to Treedonian households and firms, they are now competing with farmers in Cornucopia. Cornucopia’s loggers are in a similar predicament.

One solution would be for some or all of Treedonia’s farmers to get out of the farming business and go into some other line of work. But that is much more easily said than done. For the affected farmers it would require not just a change in job description but in their whole way of life. Entire communities would go through wrenching changes. The same thing would be happening in logging-country towns in Cornucopia. All this upheaval might be justifiable in macroeconomic terms (the concept of creative destruction is sometimes invoked), but politically it is a problem for each country’s leaders. Angry loggers in Cornucopia and angry farmers in Treedonia will demand that politicians do something about the situation.

One possible response would be for each country to make the adjustment easier for those affected. Cornucopia could pay to relocate and retrain its former loggers, and Treedonia could do the same for its former farmers. But that kind of program can get expensive very quickly, without really making anyone happy. For that reason, governments often choose instead to intervene in the markets where the trouble started. Government intervention on behalf of domestic industries is called protectionism. There are two main forms of this: subsidies and tariffs.

Subsidies

If Treedonia’s government doesn’t like the idea of paying its farmers to stop farming, it can instead pay them to keep farming. Subsidies are grants given to domestic producers to help them develop and compete with foreign producers. With subsidies, domestic producers can charge less for their goods without losing money. This kind of subsidy shifts supply to the right. A variant form of subsidy is paid to consumers instead of producers, but the subsidy is only available if the consumer buys from a domestic producer. (One example would be a tax rebate for anyone who buys a domestically produced vehicle.) This kind of subsidy shifts the demand curve for domestic products to the right. One way or another, subsidies increase domestic output while decreasing consumers’ out-of-pocket costs.

The downside of subsidies is that they cost the government money. Ultimately, subsidies have to be paid for either through higher taxes or through increased government borrowing. Neither option is attractive, but the policy choice to rely on domestic producers, instead of on the foreign producers who have the comparative advantage, brings with it a loss of economic efficiency that has to be paid for somehow.

Tariffs

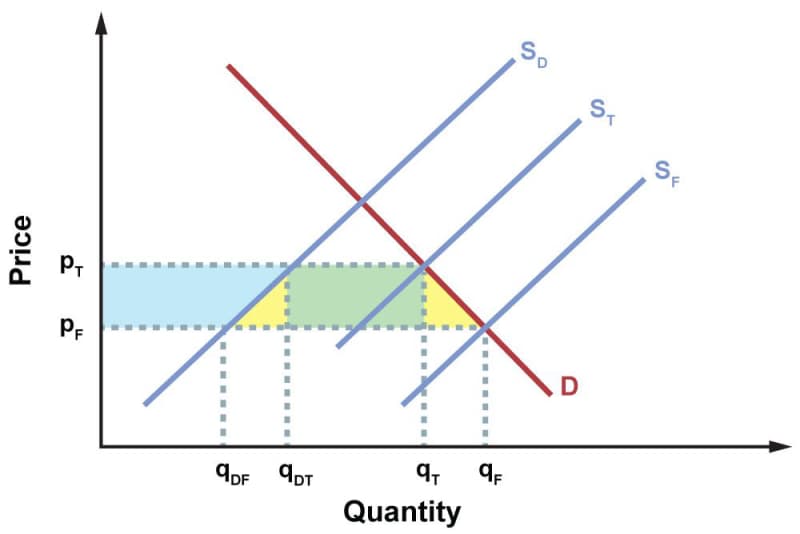

Instead of subsidizing farmers, Treedonia could impose tariffs on crops imported from Cornucopia. Tariffs, taxes paid on imported goods, are politically attractive because on paper they are win-win: they help domestic producers by increasing foreign competitors’ costs, and the tariffs generate tax revenue for the government. The reality is more complicated, however, as illustrated in the figure.

In the absence of tariffs, the free-market equilibrium quantity and price, \(q_F\) and \(p_f\), are determined by the intersection of the demand curve, \(D\), and the overall free-market supply curve, \(S_F\). The intersection of the demand curve with the domestic producers’ supply curve, \(S_D\), determines the quantity supplied by domestic producers, \(q_\text{DT}\) . The quantity imported is \(q_F\) – \(q_\text{DF}\).

Tariffs raise importers’ costs and therefore shift the overall supply curve from \(S_F\) to \(S_T\), while leaving \(S_D\) unaffected. This drops the overall quantity sold down to \(q_T\). At the same time, the curve shift drives the price for all suppliers up to \(p_T\). Domestic suppliers respond by increasing their output from \(q_\text{DF}\) to \(q_\text{DT}\). The new, smaller quantity imported is \(q_T\) – \(q_\text{DT}\).

What the figure shows is that domestic producers and the government do benefit, but this comes at the expense of domestic consumers. The colored areas together represent consumer surplus that the consumers enjoyed without tariffs but lose due to tariffs. The blue area is social welfare transferred to domestic producers, as an increase in their producer surplus. The yellow areas represent deadweight loss—social welfare that is simply lost.

The green area is tax revenue that comes out of consumers’ pockets due to the higher price. How much of the tariff comes out of the importers’ pockets? Importers will be unwilling to absorb much of the cost of tariffs when they are also supplying to a lot of other countries that don’t charge tariffs. In that case, nearly all the burden of the tariff will fall on consumers in the tariff-charging country. The supposed tax on importers will in practical effect be a tax on domestic consumers.

Quotas are a third form of government intervention. A quota for a particular imported good is a government-imposed cap on the quantity imported. True quotas are rare, but sometimes they are combined with tariffs. In such an arrangement, a good can be imported tariff-free up to a certain limit, but for any quantity above that limit a tariff is charged.