Until 2008, the reserve requirement and open market operations were the primary tools of monetary policy. The financial crisis of 2007–2009, however, brought major changes to the financial system.

Ample Reserves

In order to prop up GDP growth, the Fed added so much money to the money supply (using open market operations) that banks stopped lending out as much as they legally could. In other words, the Fed went all-in on fighting unemployment and for the time being didn’t worry about inflation. But banks, skittish about lending money to borrowers who would default on the loans, in 2008 started holding back more reserves than required. The Fed, in order to partly compensate the banks for the lost income from loans they were afraid to make, began paying the banks interest on excess reserves they kept on deposit with the Fed. This established a “new normal,” an ample reserves environment in which banks routinely held excess reserves, above the required minimum.

In this new environment, the reserve requirement lost its value as a policy tool, since the reserve requirement no longer influenced the level of reserves banks chose to hold. Additionally, economists found that the size of the M2 money supply was no longer a good indicator of the state of the economy and predictor of GDP growth. That is, M2 and GDP growth were no longer usefully correlated. In 2020, during the brief recession brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed dropped the reserve requirement altogether.

Managing the Federal Funds Rate

Today, banks are free to hold as many or few reserves as they like, and the Fed pays interest on all reserves that banks deposit with it, at a rate known as the Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) rate. The Fed has also stopped treating the size of the money supply as an important policy variable and instead concentrates simply on manipulating the federal funds rate. The Fed’s main tool for this is the new IROB rate. In an ample reserves environment, the federal funds rate tends to stay near the IROB rate. This is because (1) when reserves are plenty, banks are happy to lend to other banks at low rates, but (2) no bank will lend at a lower rate than the IROB rate when the IROB rate is always available.

If banks only borrowed money from other banks, that would be the end of the story. The IORB rate would act as a hard floor under the Federal Funds rate. However, there are other, non-bank institutions that also keep reserves on deposit at the Fed and also lend money to banks. Most of these are government-sponsored enterprises, such as the Federal National Mortgage Association (commonly known as Fannie Mae). They aren’t eligible for the IORB rate, but they are entitled to a slightly lower rate paid on reserves by the Fed, the Overnight Reserve Repurchase (ON RRP) rate. These organizations are happy to lend to banks at rates higher than the ON RRP rate but lower than the IORB rate.

Since the reported, official Federal Funds rate is calculated as an average of all the rates paid on individual loans taken out by banks, the Federal Funds rate normally ends up somewhere between the IORB rate and the ON RRP rate. The IORB and ON RRP rates are administered rates, meaning that the Fed is able to set them precisely, by direct policy action. These rates usually correspond closely to the upper and lower ends of the target range for the Federal Funds rate.

Open market operations remain part of the picture, but they are less important than they used to be. Their main use is to keep banks operating in an ample-reserves environment.

Graphical Summary

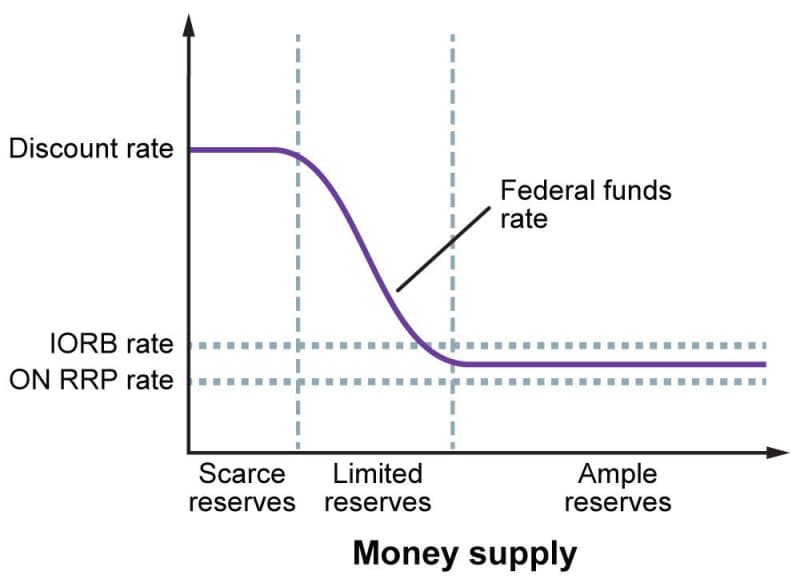

The Fed actually has not two but three administered rates. Their relationship to the Federal Funds rate is summarized in the following diagram.

Banks and the Fed may be operating in an environment where bank reserve funds are scarce, limited, or ample.

- Reserves are scarce when banks are struggling to satisfy private demand for loans while maintaining enough reserves to fulfill depositors’ withdrawal requests and to comply with any reserve requirement. In this environment, banks cannot expect to borrow from other banks. Instead, they borrow money from the Fed at the discount rate, the administered rate the Fed offers as banks’ lender of last resort. Because no bank ever needs to borrow from anyone at a rate higher than the discount rate, the discount rate puts a ceiling on the Federal Funds rate.

- Reserves are limited when banks are readily able, with careful management of their assets, to satisfy private demand for loans while maintaining adequate reserves to fulfill depositors’ withdrawal requests and to comply with any reserve requirement. In this environment, banks do not hold significant excess reserves; instead, any significant reserves are lent out to banks whose reserves are running low. The rate of these loans, the Federal Funds rate, is highly sensitive to the overall quantity of reserves in the system. Small changes in that quantity, achieved by the Fed through open market operations and adjustments to the reserve requirement, cause significant changes in the Federal Funds rate. The Fed’s administered rates do not play a major role.

- Reserves are ample when banks have little trouble satisfying private demand for loans and often have reserves left over. In this environment, banks keep their reserves on deposit with the Fed, where they earn interest at the IORB rate. When banks do need to borrow money, they can borrow from another bank at or near the IORB rate or (even better) they can borrow from a non-bank institution at a rate closer to the slightly lower ON RRP rate. Thus the Federal Funds rate generally stays in the narrow range between the IROB and ON RRP rates.

Notice that in the figure as a whole, the IORB rate is a floor: the Federal Funds rate can go higher than the IROB rate (as high as the discount rate), but it can’t go lower—at least, not much lower. But if one “zooms in” on the ample reserves part of the curve, the ON RRP rate is the floor and the IROB rate becomes the ceiling.