Economics is a science, specifically a social science. As a science, it engages in model-building and prediction. As a social science, it engages with human problems and, where possible, offers solutions.

Models

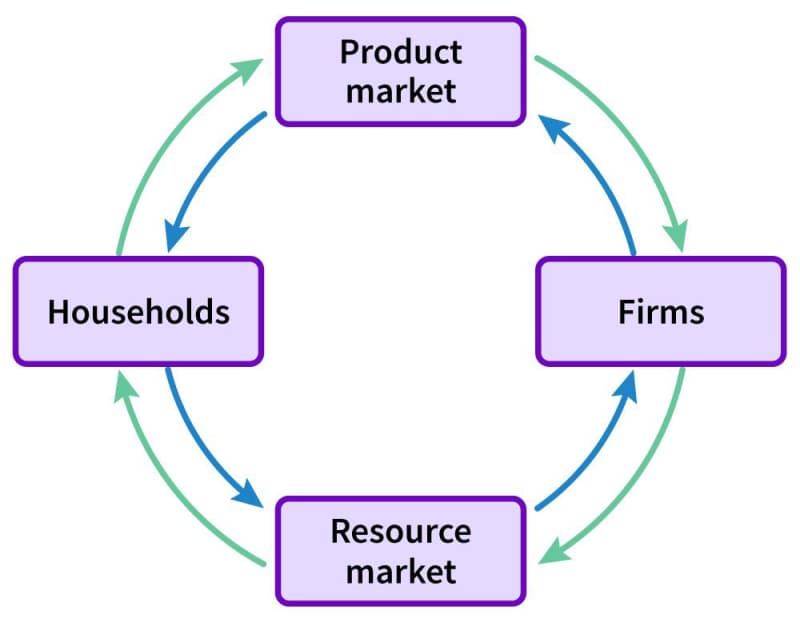

Model building is a key part of any science. Chemists build models of chemical reactions, for example, and meteorologists build models of storm systems. Economists build models of markets and of economies. The simplest model of a national economy is the circular flow model shown below.

The model contains just two sets of actors, households and firms, and two markets where those actors come together. In the product market, households are the buyers, also known as consumers. They buy goods and services from firms (all types of goods and services in a single market, because this is a macroeconomic model). Firms are the sellers, also known as the producers. The flow of products is represented by the blue arrows pointing from firms to the product market and from there to households. Households pay for the products with funds, i.e., money, represented by the green arrows leading from households back to firms.

Firms don’t create products out of nothing; they need resources. These include raw materials and machinery, but in this model the resource of interest is labor, which is provided by households. Thus the resource market in this model can be thought of as the labor market. It is where workers give their time and energy to firms (the blue arrows) in exchange for wages (the green arrows). In this market, households are the sellers and firms are the buyers.

This circular flow model is extremely simple. There’s no government, for example, and therefore no flow of funds representing taxes. And the model doesn’t even tell us very much about what it does show. For example, the model says nothing about how much money flows from households to firms. We could make the model more informative by introducing economic variables that quantify certain things. Macroeconomists work with a variable called the money supply, for example, which represents the total amount of funds in circulation. Another way to add to a model is to make assumptions. For instance, we might assume that for a certain period of time, workers’ wages remain fixed. Then we would be assuming that flows of labor and funds through the resource market remain in constant proportion.

Variables and assumptions are the bread and butter of economic theory. One kind of assumption is so common it deserves special mention: the “all else being equal” assumption—in Latin, ceteris paribus (pronounced SET-er-is PAHR-ih-bus). An economist may say, “As a good gets cheaper, all else being equal, the good will be purchased in greater quantity.” What the economist means is that as the price goes down, purchase quantity goes up, assuming there is no change in the amount of money consumers have to spend, no change in their level of need for milk, and so on.

Models are used to make predictions. Just for example, the circular flow model, minimal though it is, suggests something significant: if firms were to pay households more for labor, households would have more money to spend on products, and thus firms can expect a boost in sales. In short, higher wages encourage more consumption. In the real world, of course, things are more complicated. (Models simplify; that is both a virtue and a shortcoming.) When a model does a poor job of making predictions, the model can be revised. If the new version generates more accurate predictions, it is judged an improvement over the old version.

Positive analysis versus normative analysis

Model building, prediction, and model revision are all part of what is sometimes called positive analysis. This is simply the effort to describe, in a factual, non-judgmental way, how things are, or were, or will be. It may involve identifying cause-and-effect relationships. If a description of an economic phenomenon is correct, it tends to result in predictions that come true. Conversely, if a description generates false predictions, this suggests that the description is incorrect or at least incomplete. Normative analysis, in contrast, consists of spelling out how things ought to be. The claim that action A would produce more desirable results than action B is a normative judgment. So is the claim that a certain policy would be unfair.

Some economics texts claim that economists stick to positive analysis and consistently avoid normative analysis. But if you pay close attention, you’ll find economists making normative judgments all the time. Often, they do using terms like “detrimental,” “beneficial,” “inefficient, and “optimal.” There’s nothing wrong with this. As social scientists, economists are uniquely qualified not only to identify certain kinds of social problems but also to recommend solutions. Economics who make corporate or public policy, or advise policymakers, are in fact professionally required to engage in normative analysis.

That said, keeping the difference between positive and normative analysis in mind helps to avoid misunderstanding and wishful thinking. Suppose an economist says that a proposed rent control law will in time lead to a housing shortage. That is a piece of positive analysis. It’s a factual prediction, not a value judgment. The appropriate response is to see whether evidence can be found to support or contradict the claim—not to reject the claim on the grounds that we don’t want it to be true. If the claim turns out to be well supported by argument and/or historical data, that is something normative analysis has to take into account. Given that the law will lead to a housing shortage, do the cons of the proposed law outweigh the pros? Or is the law on balance still a good idea?