In "Five Big Ideas," we saw that the most important kind of multi-party effect is gains from trade. But when would trade be advantageous to both parties? And by how much? Before we answer those questions, we have to understand the concept of a production possibilities frontier and the difference between absolute advantage and comparative advantage.

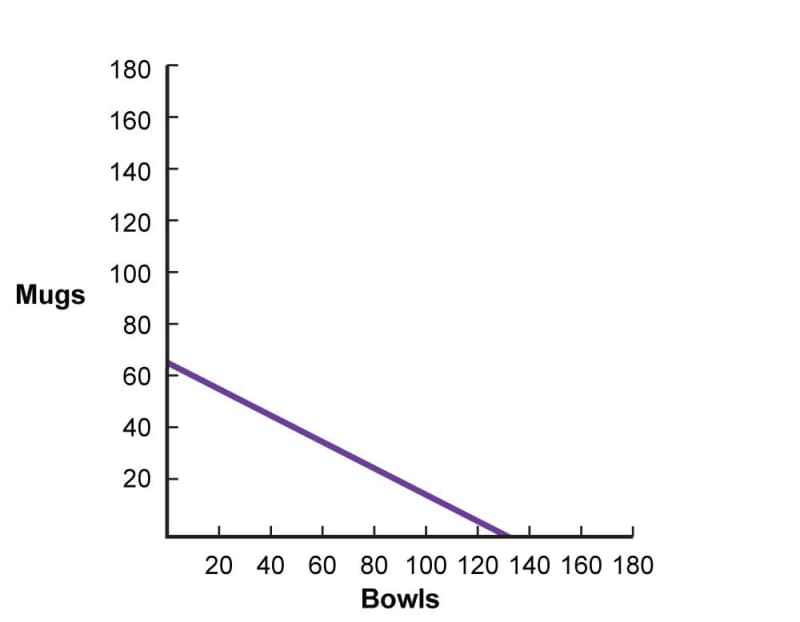

Consider a potter named Alicia, who is very experienced and therefore very skilled at making stoneware. In a day, she can make up to 150 soup bowls or 120 drinking mugs. Or she can choose to produce some combination of both goods. We can depict her options graphically, as shown below.

Every point on or below the diagonal line is a live option. For instance, in a day Alicia could make 60 bowls and 50 mugs. Every point above the line is inaccessible. Alicia can’t work fast enough to make both 100 bowls and 90 mugs in a day. The diagonal line itself is Alicia’s production possibilities frontier, or PPF for short. Along this line, she is working as hard and as efficiently as she can. She can manage 75 bowls and 60 mugs, for example, but making more mugs would require making fewer bowls, and vice versa.

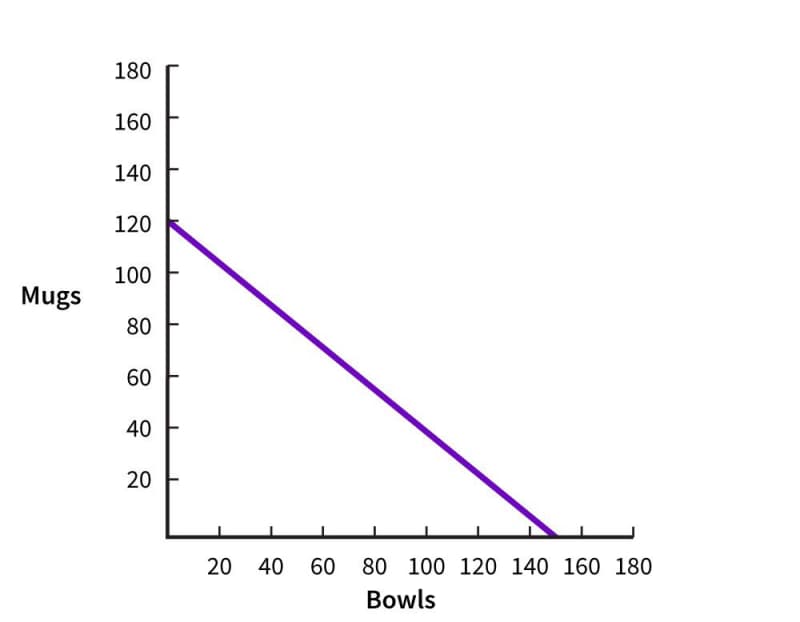

Now consider another artisan, Boris. Being less experienced than Alicia, he can make only 130 bowls or 65 mugs in a day. The quality of his work matches Alicia’s, but he can’t keep in with her in volume. His PPF looks like this.