Few people agree on exactly what “intelligence” is or how to measure it. The nature and origin of intelligence are elusive, and the value and accuracy of intelligence tests are often uncertain. Researchers who study intelligence often argue about what IQ tests really measure and whether or not Einstein’s theories and Yo-Yo Ma’s cello-playing show different types of intelligence.

Intelligence is a particularly thorny subject, since research in the field has the potential to affect many social and political decisions, such as how much funding the U.S. government should devote to educational programs. People who believe that intelligence is mainly inherited don’t see the usefulness in special educational opportunities for the underprivileged, while people who believe that environment plays a large role in intelligence tend to support such programs. The importance and effects of intelligence are clear, but intelligence does not lend itself to easy definition or explanation.

Theories of Intelligence

A typical dictionary definition of intelligence is “the capacity to acquire and apply knowledge.” Intelligence includes the ability to benefit from past experience, act purposefully, solve problems, and adapt to new situations. Intelligence can also be defined as “the ability that intelligence tests measure.” There is a long history of disagreement about what actually constitutes intelligence.

Charles Spearman proposed a general intelligence factor, g, which underlies all intelligent behavior. Many scientists still believe in a general intelligence factor that underlies the specific abilities that intelligence tests measure. Other scientists are skeptical, because people can score high on one specific ability but show weakness in others.

In the 1980s and 1990s, psychologist Howard Gardner proposed the idea of not one kind of intelligence but eight, which are relatively independent of one another. These eight types of intelligence are:

Linguistic: spoken and written language skills

Logical–mathematical: number skills

Musical: performance or composition skills

Visual-spatial: ability to evaluate and analyze the visual world

Bodily-kinesthetic: dance or athletic abilities

Interpersonal: skill in understanding and relating to others

Intrapersonal: skill in understanding the self

Naturalistic: skill in understanding the natural world

Gardner proposed that each of these domains of intelligence has inherent value, but that culture and context may cause some domains to be emphasized over others. Critics of the idea of multiple intelligences maintain that these abilities are talents rather than kinds of intelligence.

Also in the 1980s and 1990s, Robert Sternberg proposed a triarchic theory of intelligence that distinguishes among three aspects of intelligence:

Componential intelligence: the ability assessed by intelligence tests

Experiential intelligence: the ability to adapt to new situations and produce new ideas

Contextual intelligence: the ability to function effectively in daily situations

Some researchers distinguish emotional intelligence as an ability that helps people to perceive, express, understand, and regulate emotions. Other researchers maintain that this ability is a collection of personality traits such as empathy and extroversion, rather than a kind of intelligence.

Intelligence Testing

The psychometric approach to intelligence emphasizes people’s performance on standardized aptitude tests. Academic tests generally fall into two categories: aptitude tests and achievement tests. Aptitude tests predict people’s future ability to acquire skills or knowledge. Rather than focusing on accumulated knowledge, aptitude tests assess potential in areas like problem-solving, logical reasoning, or specific talents, and they are often used in contexts like college admissions or career placement. For example, the SAT and ACT are often considered aptitude tests because they aim to predict a student’s likelihood of success in college. Achievement tests, on the other hand, measure skills and knowledge that people have already learned. These tests assess learning in specific subjects, such as reading, math, or science, and are typically used to evaluate knowledge gained over a certain period. Standardized exams, like the SAT Subjects Tests or end-of-year state exams, are examples of achievement tests, as they gauge students’ grasp of material covered in the curriculum.

Types of Tests

Intelligence tests can be given individually or to groups of people. The best-known individual intelligence tests are the Binet-Simon scale, the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.

The Binet-Simon Scale

Alfred Binet and his colleague Theodore Simon devised this general test of mental ability in 1905, and it was revised in 1908 and 1911. The test yielded scores in terms of mental age.

Mental age refers to the age level at which a person is performing intellectually based on the results of an intelligence test.

Example: A 10-year-old child whose score indicates a mental age of 12 performed like a typical 12-year-old.

Chronological age is the actual age of an individual, as measured in years and months.

The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale

In 1916, Lewis Terman and his colleagues at Stanford University created the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale by expanding and revising the Binet-Simon scale. The Stanford-Binet yielded scores in terms of intelligence quotients. The intelligence quotient (IQ) is the mental age divided by the chronological age and multiplied by 100. IQ scores allowed children of different ages to be compared.

If a child’s mental age matched their chronological age, their IQ would be 100, which was considered average. If their mental age was higher than their chronological age, their IQ would be above 100, indicating above-average intelligence. Conversely, if their mental age was lower than their chronological age, their IQ would be below 100.

Example: A 10-year-old whose performance resembles that of a typical 12-year-old has an IQ of 120 (12 divided by 10 times 100).

There are two problems with the intelligence quotient approach:

- The score necessary to be in the top range of a particular age group varies, depending on age.

- The scoring system had no meaning for adults. For example, a 50-year-old man who scores like a 30-year-old can’t accurately be said to have low intelligence.

Although the original mental age formula is no longer used, chronological age is still a factor in modern intelligence testing, as age norms are established to compare an individual’s test performance to a representative sample of people in the same age group.

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

David Wechsler published the first test for assessing intelligence in adults in 1939. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale contains many items that assess nonverbal reasoning ability and therefore depends less on verbal ability than does the Stanford-Binet. It also provides separate scores of verbal intelligence and nonverbal or performance intelligence as well as a score that indicates overall intelligence.

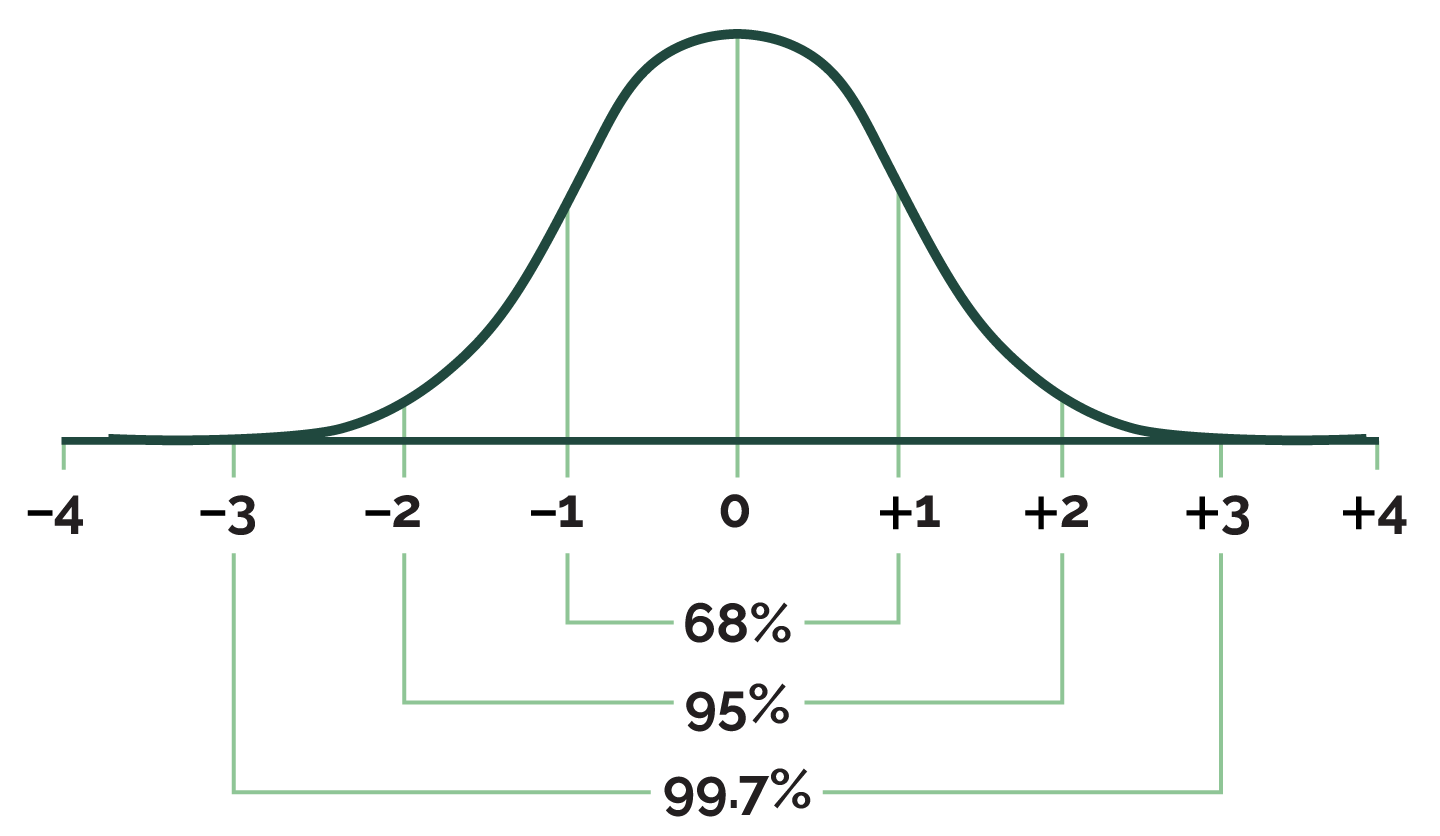

The term intelligence quotient, or IQ, is also used to describe the score on the Wechsler test. However, the Wechsler test presented scores based on a normal distribution of data rather than the intelligence quotient. The normal distribution is a symmetrical bell-shaped curve that represents how characteristics like IQ are distributed in a large population. In this scoring system, the mean IQ score is set at 100, and the standard deviation is set at 15. The test is constructed so that about two-thirds of people tested (68 percent) will score within one standard deviation of the mean, or between 85 and 115.

On the Wechsler test, the IQ score reflects where a person falls in the normal distribution of IQ scores. Therefore, this score, like the original Stanford-Binet IQ score, is a relative score, indicating how the test taker’s score compares to the scores of other people. Most current intelligence tests, including the revised versions of the Stanford-Binet, now have scoring systems based on the normal distribution. About 95 percent of the population will score between 70 and 130 (within two standard deviations from the mean), and about 99.7 percent of the population will score between 55 and 145 (within three standard deviations from the mean).

Group Intelligence Tests

Individual intelligence tests can be given only by specially trained psychologists. Such tests are expensive and time-consuming to administer, so educational institutions often use tests that can be given to a group of people at the same time. Commonly-used group intelligence tests include the Otis-Lennon School Ability Test and the Lorge-Thorndike Intelligence Test.

Biological Tests of Intelligence

Some researchers have suggested that biological indices such as reaction time and perceptual speed relate to intelligence as measured by IQ tests:

Reaction time: the amount of time a subject takes to respond to a stimulus, such as by pushing a button when a light is presented.

Perceptual speed: the amount of time a person takes to accurately perceive and discriminate between stimuli. For example, a test of perceptual speed might require a person to determine which of two lines is shorter when pairs of lines flash very briefly on a screen.

Characteristics of IQ Tests

Some characteristics of IQ tests are standardization, norms, percentile scores, standardization samples, reliability, and validity.

Standardization: Intelligence tests are standardized, which means that uniform procedures are used when administering and scoring the tests. Standardization helps to ensure that people taking a particular test all do so under the same conditions. Standardization also allows test takers to be compared, since it increases the likelihood that any difference in scores between test takers is due to ability rather than the testing environment. The SAT and ACT are two examples of standardized tests.

Norms and Percentile Scores: Researchers use norms when scoring the tests. Norms provide information about how a person’s test score compares with the scores of other test takers. Norms allow raw test scores to be converted into percentile scores. A percentile score indicates the percentage of people who achieved the same as or less than a particular score. For example, if someone answered 20 items correctly on a 30-item vocabulary test, he receives a raw score of 20. He consults the test norms and finds that a raw score of 20 corresponds with a percentile score of 90. This means that he scored the same as or higher than 90 percent of people who took the same test.

Standardization Samples: Psychologists come up with norms by giving a test to a standardization sample. A standardization sample is a large group of people that is representative of the entire population of potential test takers.

Reliability: Most intelligence tests have good reliability. Reliability is a test’s ability to yield the same results when the test is administered at different times to the same group of people. Psychologists use several types of reliability to assess the consistency of a test:

Test-retest reliability is determined by administering the same test to the same group of people on two different occasions and then comparing the scores. If the test is reliable, the two sets of results should be similar, indicating stability over time. For example, if a person takes an intelligence test and scores similarly when they retake it weeks later, this points to high test-retest reliability.

Split-half reliability measures the consistency of a test’s results by dividing the test into two equal halves and comparing the scores on each half. For example, the items in a test could be split into odd-numbered and even-numbered questions. If the two sets of scores are similar, the test has high split-half reliability, indicating that all parts of the test contribute equally to what is being measured.

Validity: Validity is a test’s ability to measure what it is supposed to measure. Although intelligence tests cannot be considered good measures of general intelligence or general mental ability, they are reasonably valid indicators of the type of intelligence that enables good academic performance. There are different types of validity that psychologists use to assess a test’s accuracy:

Construct validity refers to whether a test truly measures the concept of construct it claims to measure. For example, if a test is designed to measure intelligence, it should actually assess components associated with intelligence (like problem-solving and reasoning), rather than unrelated factors. Construct validity involves comparing the test’s results with other established measures of the same construct to see if they correlate.

Predictive validity measures how well a test can predict future performance or behavior. For instance, if a college entrance exam claims to predict students’ academic success in college, then students who score higher on the test should generally perform better in college than those who score lower. High predictive validity means that the test can reliably predict outcomes.

Critical Views on Intelligence Testing

Critics of widespread intelligence testing point out that politicians and the public in general misuse and misunderstand intelligence tests. They argue that these tests provide no information about how people go about solving problems. Also, the critics say these tests do not explain why people with low intelligence scores can function intelligently in real-life situations. Advocates of intelligence testing point out that such tests can identify children who need special help as well as gifted children who can benefit from opportunities for success.

The Influence of Culture

Many psychologists believe that cultural bias can affect intelligence tests, for the following reasons:

- Tests that are constructed primarily by white, middle-class researchers may not be equally relevant to people of all ethnic groups and economic classes.

- Cultural values and experiences can affect factors such as attitude toward exams, degree of comfort in the test setting, motivation, competitiveness, rapport with the test administrator, and comfort with problem-solving independently rather than as part of a team effort.

- Cultural stereotypes can affect the motivation to perform well on tests.

In order to understand and reduce cultural bias in intelligence testing, researchers aim to address factors such as:

Cultural relevance: Many standard intelligence tests contain content and problem-solving approaches more familiar to people raised in certain cultural settings, especially those from Western, middle-class backgrounds. To make intelligence tests more fair, researchers seek to design questions that do not rely on culturally-specific knowledge or experiences.

Test taker experience and attitudes: Cultural values and experiences shape attitudes toward exams, comfort levels in test environments, and motivation. For instance, individuals from collectivistic cultures might find it more intuitive to solve problems collaboratively rather than independently. Similarly, cultural factors can affect rapport with the test administrators, willingness to engage in competitive tasks, and comfort with standard test structures.

Stereotype threat: Stereotype threat refers to the anxiety and reduced performance that can occur when individuals feel they are being judged based on negative stereotypes about their social group. Research shows that people who feel subject to stereotypes – such as women in STEM fields or racial minorities on intelligence tests – may perform below their actual abilities due to stress and self-doubt.

Stereotype Lift: On the other hand, stereotype lift can occur when certain groups benefit from positive stereotypes, which can improve their confidence and performance. For example, a stereotype that assumes a particular group is “naturally good” at a skill could subconsciously boost the group’s performance.

The following describes a number of considerations and ways in which tests can be designed to be culturally sensitive and minimize performance differences linked to stereotypes:

Using culturally-neutral content: Avoiding questions or scenarios that assume specific cultural knowledge or experiences, such as references to activities, slang, or historical figures that might not be familiar to everyone.

Adapting language: Ensuring that language used in the test is straightforward, clear, and universally understandable, and avoiding idioms or phrases that may be confusing to non-native speakers or those from different cultural backgrounds.

Anonymity and neutral test settings: Some tests are structured to be anonymous or are set up in ways that avoid asking demographic information (like race or gender) at the start, which reduces the chance that a test taker’s awareness of stereotypes about their group could impact their performance. Demographic questions can be asked at the end of the test or outside of the testing environment.

Neutral, positive framing of test purpose: Researchers can frame the test as a measure of specific, trainable skills (like problem-solving or logic) rather than as a measure of innate intelligence or talent. This reduces stereotype-related pressure, as test takers are less likely to see the test as a judgment of their abilities tied to personal or group identity.

Counter-stereotypical examples: In some contexts, researchers use examples in test instructions or materials that reflect diverse role models or figures excelling in areas traditionally stereotyped. This helps reduce internalized bias by subtly showing that success is not limited to a certain demographic.

Practice tests and familiarization: Offering practice sessions or study materials helps level the playing field by ensuring that all test takers, regardless of background, know what to expect and feel comfortable with the test format and content.

Adaptive testing format: Using computer-adaptive testing that adjusts difficulty based on responses can help reduce anxiety and pressure, as each person can proceed at his or her own pace and on his or her own level, minimizing pressure to perform “at a group standard.”

The Influence of Heredity and Environment

Today, researchers generally agree that heredity and environment have an interactive influence on intelligence. Many researchers believe that there is a reaction range to IQ, which refers to the limits placed on IQ by heredity. Heredity places an upper and lower limit on the IQ that can be attained by a given person. The environment determines where within these limits the person’s IQ will lie.

Despite the prevailing view that both heredity and environment influence intelligence, researchers still have different opinions about how much each contributes and how they interact.

Hereditary Influences

Evidence for hereditary influences on intelligence comes from the following observations:

- Family studies show that intelligence tends to run in families.

- Twin studies show a higher correlation between identical twins in IQ than between fraternal twins. This holds true even when identical twins reared apart are compared to fraternal twins reared together.

- Adoption studies show that adopted children somewhat resemble their biological parents in intelligence.

Family studies, twin studies, and adoption studies, however, are not without problems. For example, these studies can’t easily separate genetic influences from environmental ones, as family members often share similar environments.

Heritability of Intelligence

Heritability is a mathematical estimate that indicates how much of a trait’s variation in a population can be attributed to genes. Estimates of the heritability of intelligence vary, depending on the methods used. Most researchers believe that heritability of intelligence is between 60 percent and 80 percent.

Heritability estimates apply only to groups on which the estimates are based. So far, heritability estimates have been based mostly on studies using white, middle-class subjects. Even if heritability of IQ is high, heredity does not necessarily account for differences between groups. Three important factors limit heritability estimates:

- Heritability estimates don’t reveal anything about the extent to which genes influence a single person’s traits.

- Heritability depends on how similar the environment is for a group of people.

- Even with high heritability, a trait can still be influenced by environment.

Environmental Influences

Evidence for environmental influences on intelligence comes from the following observations:

- Adoption studies demonstrate that adopted children show some similarity in IQ to their adoptive parents.

- Adoption studies also show that siblings reared together are more similar in IQ than siblings reared apart. This is true even when identical twins reared together are compared to identical twins reared apart.

- Biologically unrelated children raised together in the same home have some similarity in IQ.

- IQ declines over time in children raised in deprived environments, such as understaffed orphanages or circumstances of poverty and isolation. Conversely, IQ improves in children who leave deprived environments and enter enriched environments.

People’s performance on IQ tests has improved over time in industrialized countries. This strange phenomenon, which is known as the Flynn effect, is attributed to environmental influences. It cannot be due to heredity, because the world’s gene pool could not have changed in the 70 years or so since IQ testing began.

Possible Causes of the Flynn Effect

The precise cause for the Flynn effect is unclear. Researchers speculate that it may be due to environmental factors such as decreased prevalence of severe malnutrition among children, enhancing of skills through television and video games, improved schools, smaller family sizes, higher level of parental education, or improvements in parenting.

Cultural and Ethnic Differences

Studies have shown a discrepancy in average IQ scores between whites and minority groups in the United States. Black, Native American, and Hispanic people score lower, on average, than white people on standardized IQ tests. Controversy exists about whether this difference is due to heredity or environment.

Hereditary Explanations

A few well-known proponents support hereditary explanations for cultural and ethnic differences in IQ:

- In the late 1960s, researcher Arthur Jensen created a storm of controversy by proposing that ethnic differences in intelligence are due to heredity. He based his argument on his own estimate of about 80 percent heritability for intelligence.

- In the 1990s, researchers Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray created a similar controversy with their book, The Bell Curve. They also suggested that intelligence is largely inherited and that heredity at least partly contributes to ethnic and cultural differences.

Environmental Explanations

Many researchers believe that environmental factors primarily cause cultural and ethnic differences. They argue that because of a history of discrimination, minority groups comprise a disproportionately large part of the lower social classes, and therefore cultural and ethnic differences in intelligence are really differences among social classes. People in lower social classes have a relatively deprived environment. Children may have:

- Fewer learning resources

- Less privacy for study

- Less parental assistance

- Poorer role models

- Lower-quality schools

- Less motivation to excel intellectually

Some researchers argue that IQ tests are biased against minority groups and thus cause the apparent cultural and ethnic differences.

However, not all minority groups score lower than whites on IQ tests. Asian Americans achieve a slightly higher IQ score, on average, than whites, and they also show better school performance. Researchers suggest that this difference is due to Asian American cultural values that encourage educational achievement.

It is also important to note that IQ scores show greater variability within groups than between groups, meaning that individual differences are often more significant than differences between distinct populations. Understanding that IQ scores are influenced by a broad set of environmental and societal factors is essential in interpreting these scores fairly and responsibly.

Access and Opportunity

Intelligence test scores have historically been used as gatekeepers for various opportunities, including employment, military service, education, and even immigration to the United States. In the early- to mid-20th century, intelligence testing became a common method for determining eligibility and access in these areas. For example, IQ scores were once used by the military to determine suitability for promotion in rank, with higher scores often associated with eligibility for advanced roles and responsibilities.

In education, intelligence tests have also been used to screen students for certain programs, often determining admission into gifted programs or specialized academic tracks. While these tests aim to match students with the resources and challenges that suit their abilities, they may unintentionally limit opportunities for individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds, who might perform lower on standardized tests due to socioeconomic or educational inequalities rather than a lack of cognitive ability.

Additionally, in the early-20th century, intelligence testing influenced U.S. immigration policies. Some policies sought to restrict entry from certain countries based on perceived intelligence levels, which were often measured using culturally biased tests. These practices were criticized for promoting exclusionary policies based on limited understandings of intelligence and cultural background, and they fueled debates about fairness, cultural bias, and the ethical use of intelligence testing.

Fixed versus Growth Mindset

Psychologist Carol Dweck introduced the concepts of “fixed mindset” and “growth mindset” to explain how beliefs about the nature of intelligence influence learning.

A fixed mindset is the belief that intelligence is a static trait which cannot be significantly changed. People with a fixed mindset may believe that their intelligence is an inherent quality, leading them to avoid challenges or give up when faced with difficulty, as they view effort as fruitless. Students with a fixed mindset may be less motivated to improve because they see their abilities as predetermined. They might avoid tasks where they could fail, as failure is perceived as a reflection of their innate intelligence.

A growth mindset is the belief that intelligence can be developed over time through effort, learning, and practice. Individuals with a growth mindset are more likely to embrace challenges, persist in the face of setbacks, and view effort as a pathway to mastery. Students with a growth mindset are more likely to embrace learning opportunities and persist through difficulties, because they believe their efforts will lead to improvement. They tend to see mistakes as learning experiences, which can help them develop their skills and intelligence over time.

According to Dweck, students who adopt a growth mindset are more likely to achieve higher academic success, suggesting that beliefs about intelligence can influence learning outcomes.