When might Alicia and Boris each have to choose whether to make bowls or mugs? Suppose that the two artisans put their heads together and look for a way to each increase their output through cooperative trade, each day exchanging bowls made by one person for mugs from the other. Who should make the bowls, who should make the mugs, and how many of each should be traded? (Notice the word “should,” an indicator that we’re starting to think normatively.) Because Boris has the comparative advantage in making bowls, he’s the one whose time is best spend doing that. That is, Boris should specialize in bowls and use Alicia as his mug supplier.

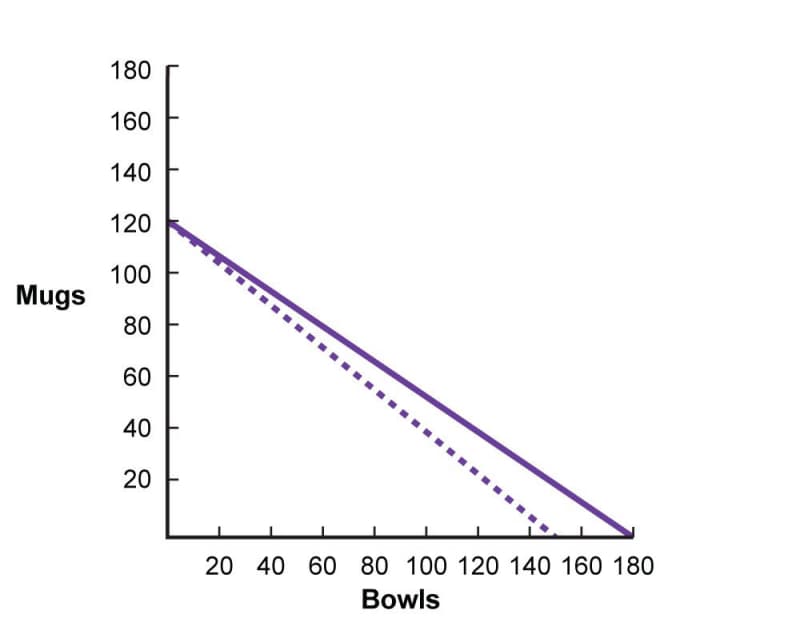

We can demonstrate the benefits of this arrangement by looking at the effect on the possibilities frontiers. If Alicia wants to produce as many mugs as possible, Boris can’t help her. She should just concentrate on mugs and make 120 of them per day. But if she wants to produce as many bowls as possible, she can have Boris make 130 bowls and trade them for, say, 80 mugs that she makes. Those 80 mugs take her 2/3 of a day (\(80/120 = 2/3\)) and leave her enough time to make 50 bowls (\(1/3 \times150 =50\)) for a total of \(130 + 50 = 180\) bowls. That’s more than the 150 she could make by herself.

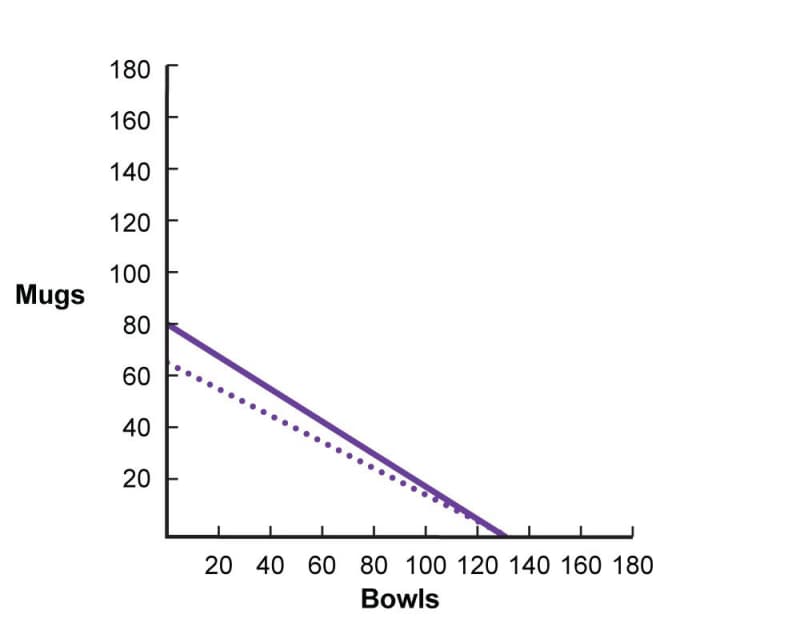

Boris benefits from the trade deal in much the same way. If he wants to produce as many bowls as possible, he can’t expect help from Alicia. His maximum bowl output remains at 130. But if he wants to produce as many mugs as possible, he can concentrate on making 130 bowls every day and give them all to Alicia in return for 80 mugs.

The changes result in a pair of PPFs that look like this:

We’ve been assuming that Alicia gives Boris 80 mugs in exchange for 130 bowls, but there’s nothing special about that exact ratio. All that’s required for the trade to be mutually beneficial is that the mugs-to-bowls ratio lie between 0.8, the opportunity cost in mugs of 1 bowl for Alicia, and 0.5, the opportunity cost in mugs of 1 bowl for Boris. If the ratio is above 0.8, Alicia will say, “I can produce bowls faster by making them myself than by making mugs to trade for bowls.” And if the ratio is below 0.5, Boris will say, “I can produce mugs faster by making them myself than by making bowls to trade for mugs.” The ratio 80 to 130 is equal to about 0.62, within the range that makes the trade between Alicia and Boris a win-win arrangement.

If the mugs-to-bowls ratio can be anything above 0.5 and less than 0.8, how does the exact ratio get decided? Alicia and Boris might reach an agreement based on a shared sense of what’s fair, or there might be some haggling in which each side threatens to walk away from a deal that’s too lopsided.