Social development significantly impacts behavior and mental processes. From early childhood, when family and caregivers influence self-concept and emotional regulation, to adulthood, when social networks and cultural values shape identity and decision-making, social interactions are fundamental to psychological development. Understanding the impact of our social connections and communities provides insight into how behavior is shaped by immediate relationships and larger social systems that contribute to emotional growth and mental health.

Ecological Systems Theory

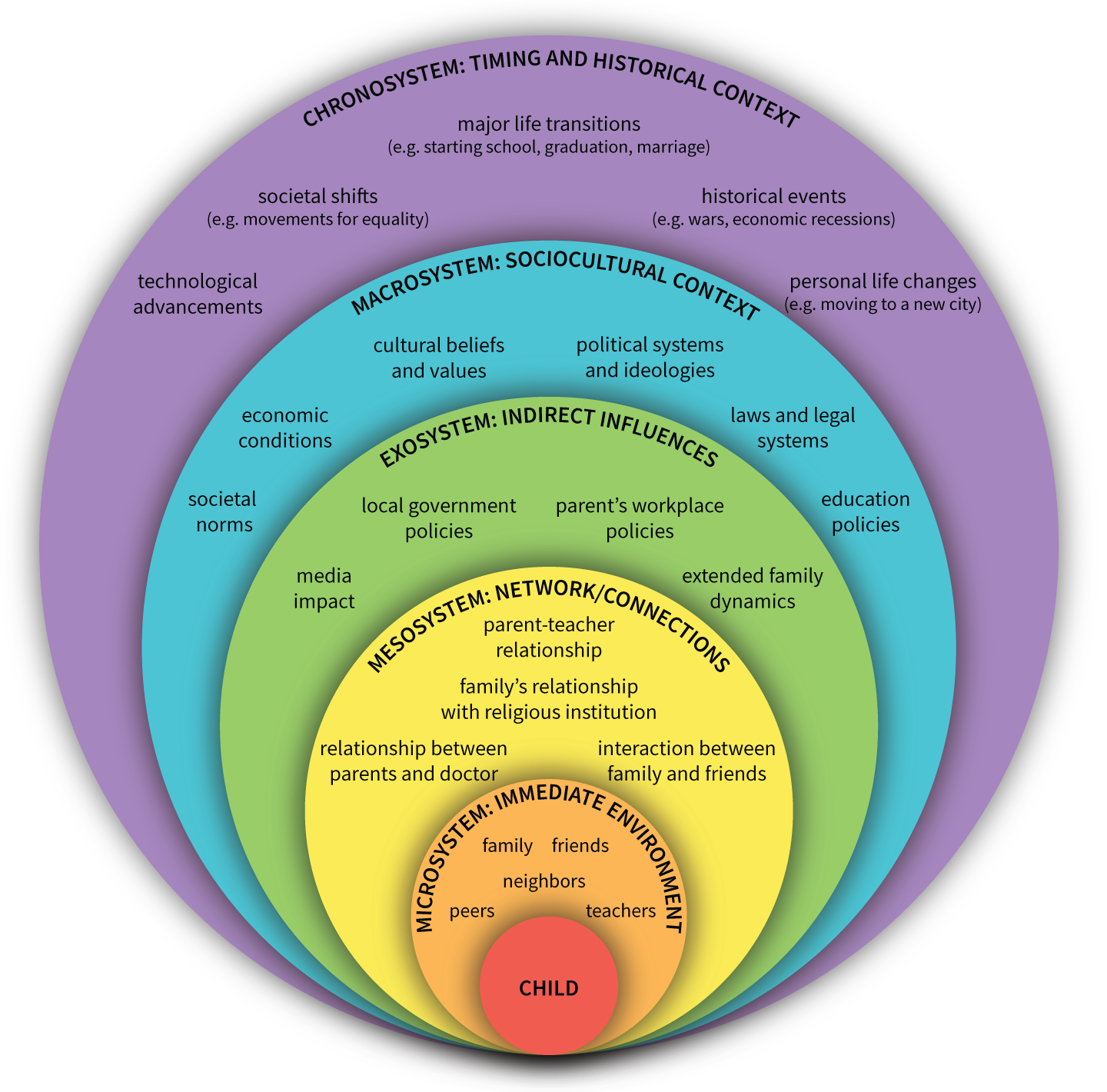

Ecological systems theory, developed by psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner, examines how various layers of the social environment influence an individual’s development. This theory proposes that social development is shaped by a set of interrelated systems, each of which plays a unique role in influencing behavior and mental processes. According to Bronfenbrenner, individuals are not isolated in their development. Rather, they are part of a complex web of environments that affect them directly and indirectly.

Bronfenbrenner’s theory proposes five systems of interaction that influence human development: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem.

The microsystem is the innermost layer. It includes those that have direct contact with the individual, such as family, friends, school, and peers. This system is the immediate surrounding environment with which a person interacts regularly, and it significantly impacts behavior, beliefs, and attitudes. For example, a supportive family environment can foster a sense of security and confidence, while interaction with peers further helps children develop social skills and empathy. The microsystem emphasizes the importance of close relationships and daily interactions in influencing emotional and social development.

The mesosystem includes the relationships between different groups within the microsystem. It reflects how these relationships interact to shape the individual’s experiences. For instance, a child’s academic success may depend not only on their interactions with teachers (microsystem) at school but also on the relationship between their parents and teachers (mesosystem). Communication and collaboration between a child’s school and family can reinforce values and provide consistent support, while conflicts between these groups may create tension and affect the child’s behavior. The mesosystem highlights that individual development is not solely influenced by separate environments but also by how these environments work together.

The exosystem includes factors that indirectly affect the individual. These are settings in which the individual does not actively participate but which still influence their development. For instance, a parent’s workplace policies, such as flexible hours or demanding schedules, can indirectly impact a child’s emotional well-being and behavior by affecting the parent’s availability and stress levels. Community resources, local government policies, and the socioeconomic conditions of the neighborhood are also part of the exosystem. This system underscores how seemingly distant factors can shape an individual’s environment and social development.

The macrosystem includes the broader cultural and societal influences that affect an individual, such as cultural norms, values, laws, and beliefs that influence attitudes and expectations within the community. For instance, a culture that values education highly will shape schools, workplaces, and family attitudes toward academic success. Similarly, cultural views on gender roles, independence, and authority can affect behavior, shaping how people interact within other systems. This differs from the previous systems in that it does not refer to an individual’s specific environment but the established society and culture within which an individual finds themselves.

The chronosystem refers to the timing of events in an individual’s life and the historical context of his or her development. This system includes the impact of life transitions, such as starting school, entering adolescence, or moving to a new city as well as more significant historical events, like economic recessions or technological advances. For example, a teenager growing up in the digital age has different developmental experiences and challenges from someone who grew up before the internet. The chronosystem acknowledges that individual development is influenced by both personal milestones and broader societal changes over time. Another example is the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly impacted the development of children who experienced disruptions in their education (school closures and distance learning), changes in family dynamics (shifts to remote work), and altered social interactions (social distancing).

Parenting Styles

Psychotherapist Diana Baumrind identified three parenting styles: authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive. Each style is characterized by different levels of responsiveness (warmth and support) and demandingness (expectations and discipline). Each has a unique impact on children’s social and emotional development. Furthermore, the impact of each parenting style can vary widely depending on cultural norms, values, and expectations regarding family roles, obedience, and independence.

Authoritarian parenting is characterized by high demands and low responsiveness. Authoritarian parents enforce strict rules, expect obedience, and may use punitive measures to ensure compliance. They value order, discipline, and respect for authority but often do not encourage open communication. Children of authoritarian parents in individualistic cultures may develop a strong sense of discipline and respect for authority but usually exhibit lower self-esteem, higher anxiety, and less social competence. They may also have difficulty expressing themselves or making independent decisions. In contrast, in collectivist cultures, authoritarian parenting can sometimes have a different outcome. In these cultures, respect for authority, family hierarchy, and obedience to parents are deeply-embedded values. Thus, authoritarian parenting may be viewed as supportive and protective rather than overly restrictive. Studies suggest that children in these contexts may develop strong family bonds, discipline, and a sense of responsibility as the authoritarian approach aligns with broader cultural expectations.

Authoritative parenting is characterized by high demands and high responsiveness. Authoritative parents set clear expectations and rules but are also warm, supportive, and open to discussion. They encourage independence while providing structure and guidance. Authoritative parenting is generally associated with positive outcomes, including higher self-esteem, better academic performance, and strong social skills. Children of authoritative parents tend to be self-disciplined, cooperative, and confident, as this style balances structure and nurturance.

This parenting style is associated with positive outcomes in most cultures. However, the emphasis on autonomy and independence may be more pronounced in individualistic cultures, where children are encouraged to explore and express their unique identities. In these cultures, authoritative parenting fosters self-confidence, resilience, and strong social skills. In collectivist cultures, authoritative parenting might focus less on individual independence and more on interdependence, responsibility to family, and social harmony. Here, the warmth and responsiveness characteristic of authoritative parenting remain beneficial, but the approach may place greater emphasis on family cohesion and respect for social norms rather than on personal autonomy. This adaptation reflects a balance between nurturing children’s well-being and upholding cultural values.

Permissive parenting is characterized by low demands and high responsiveness. Permissive parents are indulgent, providing few rules or expectations, and often avoid enforcing discipline. They are warm and nurturing, focusing on allowing children freedom and self-expression. While children of permissive parents may feel loved and supported, they often struggle with self-discipline, responsibility, and authority. They may exhibit impulsivity, encounter difficulties in structured settings, and have challenges with rules and boundaries.

This parenting style has varied effects across cultures. In cultures that value individualism and self-expression, permissive parenting may support creativity and independence but can also lead to challenges with self-discipline and adapting to structured environments. Children raised in permissive households in these cultures may experience issues with boundaries and may struggle with authority. In more collectivist societies, however, permissive parenting is less common, as the lack of structure may conflict with cultural expectations for obedience and respect for elders. In these cultures, permissive parenting may be associated with poorer outcomes, as children might find it difficult to navigate social expectations without clear guidance and boundaries.

Attachment

Attachment styles describe how infants and children interact with caregivers, especially during stress or separation. These styles, which can vary across cultures, impact children’s sense of security and future relationships. Additionally, temperament, or the child’s natural disposition, plays a role in shaping attachment, as children’s individual traits influence how they bond with their caregivers. Research on attachment styles has revealed that the bonds formed between infants and their caregivers significantly influence emotional and social development.

The concept of attachment styles was first developed by Mary Ainsworth, a developmental psychologist who expanded upon John Bowlby’s attachment theory. Bowlby initially proposed the theory of attachment, emphasizing that the bond between infant and caregiver is crucial for the child’s emotional and social development. Mary Ainsworth further advanced Bowlby’s theory through her landmark study, the Strange Situation experiment. In the Strange Situation, an infant (usually between 12 and 18 months old) and the infant’s caregiver are placed in a room containing toys. The experiment, which lasts about 20 minutes, consists of exposing the infant to a series of eight situations for about three minutes each, where the caregiver and a stranger take turns entering and leaving the room. The episodes are as follows:

- The caregiver and infant enter the room, and the infant is encouraged to explore.

- A stranger enters the room and interacts briefly with the caregiver and the infant.

- The caregiver exits the room, leaving the infant alone with the stranger.

- The caregiver returns, and the stranger leaves, reuniting the infant and caregiver.

- The caregiver exits the room again, leaving the infant completely alone.

- The stranger returns and tries to comfort the infant.

- The caregiver returns, and the stranger leaves, providing a second reunion.

Ainsworth observed and recorded the infants’ reactions during these episodes, focusing mainly on how they responded to the caregiver’s departures and returns. Based on the infants’ responses, Ainsworth identified several attachment styles:

Secure Attachment: Securely attached infants show distress when the caregiver leaves but are quickly comforted upon the caregivers’ return. They feel safe exploring the environment when the caregiver is present, indicating confidence in the caregiver’s responsiveness and support. Children with secure attachment feel confident in their caregivers’ availability and responsiveness. When a caregiver is present, securely-attached children confidently explore their environment, knowing they can return to the caregiver for comfort if needed. In studies like this, securely-attached children show mild distress when separated from their caregivers but are easily comforted upon reunion. Secure attachment is associated with positive social, emotional, and cognitive development and is more likely when caregivers are consistently responsive and nurturing.

Insecure Avoidant Attachment: Avoidant infants appear indifferent to the caregiver’s departure and return, often showing little emotional response. They may actively avoid or ignore the caregiver, suggesting a lack of trust in the caregiver’s availability. Children with avoidant attachment may seem self-reliant but may lack trust in others, often resulting from inconsistent or emotionally distant caregiving.

Insecure Anxious Attachment: Ainsworth originally called this attachment style “insecure-resistant,” but it has also been referred to as “anxious-ambivalent” attachment. Anxious infants appear very distressed when the caregiver leaves and may have difficulty calming down upon reunion. They may cling to the caregiver but resist comforting, indicating an inconsistent attachment relationship. This attachment style can result from unpredictable caregiving, which leaves the child uncertain about the caregiver’s availability.

Disorganized Attachment: This attachment style was added later by other researchers. Infants with disorganized attachment display confused or contradictory behaviors, such as approaching the caregiver but also pulling away. They may appear fearful or confused. Their reactions reflect a lack of clear strategy for dealing with stress or separation from the caregiver. This attachment style is often linked to trauma or neglect and is associated with significant emotional and behavioral challenges.

Cultural norms can influence how attachment styles manifest. In collectivist cultures where interdependence is emphasized, children may be more likely to display behaviors associated with anxious attachment, as they are accustomed to close proximity to caregivers. In individualistic cultures that value independence, avoidant attachment may appear more common, as children are often encouraged to explore independently from an early age.

Temperament and Attachment

Temperament refers to a child’s natural disposition and affects how attachment styles develop. For example, children with easygoing temperaments may bond more easily with caregivers, while those with more difficult temperaments may require additional support to form secure attachments. While caregivers play a critical role in attachment, the child’s personality traits contribute to how they respond to and perceive their caregiver’s behavior.

Separation Anxiety

Separation anxiety refers to the distress that children experience when separated from their primary caregiver or when faced with unfamiliar people. It typically emerges around six to eight months of age and peaks between ages one and two. Separation anxiety is a natural part of developing attachment, as children recognize their dependence on their caregivers for comfort and security. While secure attachment generally results in manageable separation anxiety, insecure attachment – particularly anxious attachment – can amplify children’s fear and anxiety during separation.

Harry Harlow Monkey Experiments

The importance of attachment was famously demonstrated in Harry Harlow’s studies of infant monkeys, highlighting the role of comfort over sustenance in forming bonds. Harlow raised orphaned baby rhesus monkeys and studied their behavior. Each baby monkey had two substitute, or surrogate, “mothers” instead of its natural mother. One mother was constructed of wire and wood. The other mother had the same construction except that foam rubber and terry cloth covered its wire frame. The monkeys were assigned two conditions. In one, the wire surrogate mother had a feeding bottle, and the terry cloth surrogate mother did not. In the second, the terry cloth surrogate mother had a feeding bottle, and the wire surrogate mother did not. Harlow found that the baby monkeys greatly preferred the terry cloth surrogate mother in both cases, even when the wire surrogate mother had the feeding bottle. They clung to the cloth mother even between feedings and went to it for comfort when they felt afraid.

Harlow’s findings emphasized that attachment is rooted not only in basic needs like food but also in the emotional comfort and security provided by a caregiver. These studies supported the claim that physical closeness and warmth are essential to healthy attachment, which has since influenced approaches to caregiving and the understanding of attachment in humans.

Development of Peer Relationships

Peer relationships are vital in social development, shaping behavior, self-concept, and emotional growth from early childhood through adolescence. Developmental psychologists study how children’s interactions with peers evolve over time, examining how these relationships contribute to social skills, empathy, and identity. As children age, they progressively rely on peer connections, shifting from play-based interactions in early childhood to more complex social dynamics in adolescence.

Peer Relationships in Childhood

In early childhood, children engage with peers primarily through play, which serves as a foundation for developing social skills and understanding others’ perspectives. During this stage, two key types of play are parallel play and pretend play. Parallel play occurs when children play alongside each other without directly interacting, often observing one another while focusing on their individual activities. This type of play is common in toddlers and early preschoolers and is an early step in learning to share space and toys with others.

As children develop, pretend play becomes common. In pretend play, children engage in imaginative scenarios – such as pretending to be superheroes, animals, or other family members – encouraging creativity, empathy, and role-taking. Pretend play allows children to experiment with different social roles, negotiate shared scenarios, and practice cooperation and conflict resolution. Through these early peer interactions, children begin to develop an understanding of social norms, empathy, and the give-and-take required in relationships.

Peer Relationships in Adolescence

During adolescence, peer relationships become increasingly central to social and emotional life. Adolescents gradually rely more on peers than family members for emotional support and validation as friendships deepen and peer groups grow in significance. These connections give adolescents a sense of belonging and contribute to their self-identity. Through peer interactions, adolescents also begin to navigate complex social dynamics, including friendship loyalty, group norms, and self-disclosure, which help them build social skills for adulthood.

Egocentrism in adolescence is a normal part of social-emotional development. Egocentrism, as experienced in adolescence, refers to a heightened focus on oneself and others’ perceptions of oneself. Two key components of adolescent egocentrism are:

Imaginary audience: The imaginary audience refers to adolescents’ belief that they are constantly being watched, judged, and scrutinized by others, often leading to heightened self-consciousness. Adolescents may feel as though their every action, appearance, or mistake is under intense peer scrutiny, which can result in both social anxiety and a strong need for peer approval. The imaginary audience reflects adolescents’ growing social awareness but also their tendency to overestimate others’ interest in their actions.

Personal Fable: The personal fable is the belief that one’s experiences and feelings are unique and unlike anyone else's. Adolescents may feel that their thoughts, emotions, or struggles are extraordinary, leading them to believe that others cannot fully understand them. This sense of uniqueness can result in feelings of isolation but also a sense of invincibility, as adolescents may assume that risks or consequences that apply to others do not apply to them.

These cognitive distortions, though temporary, highlight the developing self-concept and the increasing role of social comparison in adolescence. Peer relationships play a crucial role in shaping both positive social behaviors and complex self-reflective thought processes as adolescents balance individuality and belonging.

Social Development in Adulthood

Social development continues to evolve throughout adulthood as individuals form new relationships, navigate experiences within their cultural environment, and establish a sense of identity in the context of adult responsibilities and milestones. Developmental psychologists study how social roles and connections shift over time, observing how factors such as culture, attachment style, and relationship dynamics influence social well-being and personal growth in adulthood.

Culture plays a significant role in defining when adulthood begins and determining the timing of major life events. This culturally specific timeline, often called the social clock, reflects societal expectations about the appropriate ages for milestones such as finishing education, starting a career, marrying, and having children. In many Western cultures, individuals are encouraged to pursue education and career goals before marriage or parenthood, while other cultures may prioritize family formation at an earlier age. Deviating from the social clock can sometimes lead to social pressure or a sense of being “off-schedule,” which can affect self-esteem and personal satisfaction.

In some cultures, emerging adulthood is a developmental stage between adolescence and full adulthood, typically spanning the ages of 18 to 25. During this time, individuals explore identity, career paths, and relationships while delaying long-term commitments associated with traditional adulthood. Emerging adulthood is particularly common in societies where higher education, delayed marriage, and prolonged career exploration are encouraged. This transitional period allows young adults the freedom to explore their identities and goals, providing a bridge between adolescence and the responsibilities of adulthood. Emerging adulthood is more prominent in Western industrialized cultures like the United States, Canada, Australia, and many Western European countries. In contrast, non-Western and more traditional cultures often have a more direct transition from adolescence to adulthood, for example, in many parts of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, where young adults often assume adult roles earlier.

Adult Relationships

As adults form social connections and establish relationships, they create families or family-like relationships that provide mutual support and care. These relationships may include partners, close friends, or chosen family members, and they often become central sources of emotional support, security, and stability in adulthood. Forming and maintaining these bonds is a critical aspect of social development, as these connections contribute to life satisfaction, resilience, and well-being.

An individual’s childhood attachment style can influence how they form and maintain adult relationships. People who developed secure attachments as children tend to create healthy, trusting, and interdependent relationships in adulthood. They are generally comfortable with closeness and rely on others for support while maintaining independence. Conversely, those with insecure attachment styles (avoidant, anxious, or disorganized) may encounter challenges in adult relationships. For instance, adults with an avoidant attachment style may struggle with intimacy or feel uncomfortable relying on others, while those with an anxious attachment style may fear abandonment and seek constant reassurance. Disorganized attachment in childhood may lead to difficulty trusting others or maintaining stable relationships in adulthood.

Erik Erikson’s Theory of Psychosocial Development

Like Freud, Erik Erikson believed in the importance of early childhood. However, Erikson believed that personality development happens over the entire course of a person’s life. In the early 1960s, Erikson proposed a theory that describes eight distinct stages of development. His theory of psychosocial development is a reconceptualization of Freud’s psychosexual theory, expanded to emphasize the social and emotional challenges that individuals face throughout their lifespan. According to Erikson, in each stage people face new challenges, and the stage’s outcome depends on how people handle these challenges. Unlike Freud’s focus on early childhood, Erikson’s theory spans from infancy to late adulthood. Each stage presents a unique psychosocial conflict. Successful resolution of these conflicts leads to the development of essential virtues, such as hope, autonomy, and identity, which contribute to psychological resilience and social competence. However, if a conflict remains unresolved, it may hinder the individual’s ability to cope with later challenges, potentially leading to issues in personal relationships, self-esteem, or overall well-being. Erikson named the stages according to these possible outcomes:

Stage 1: Trust versus Mistrust

In the first year after birth, babies depend completely on adults for basic needs such as food, comfort, and warmth. If the caretakers meet these needs reliably, the babies become attached and develop a sense of security. Otherwise, they may develop a mistrustful, insecure attitude.

Stage 2: Autonomy versus Shame and Doubt

Between the ages of one and three, toddlers start to gain independence and learn skills such as toilet training, feeding themselves, and dressing themselves. Depending on how they face these challenges, toddlers can develop a sense of autonomy or a sense of doubt and shame about themselves.

Stage 3: Initiative versus Guilt

Between the ages of three and six, children must learn to control their impulses and act in a socially responsible way. If they can do this effectively, children become more self-confident. If not, they may develop a strong sense of guilt.

Stage 4: Industry versus Inferiority

Between the ages of six and 12, children compete with peers in school and prepare to take on adult roles. They end this stage with either a sense of competence or a sense of inferiority.

Stage 5: Identity versus Role Confusion

During adolescence, which is the period between puberty and adulthood, children try to determine their identity and their direction in life. Depending on their success, they either acquire a sense of identity or remain uncertain about their roles in life.

Stage 6: Intimacy versus Isolation

In young adulthood, people face the challenge of developing intimate relationships with others. If they do not succeed, they may become isolated and lonely.

Stage 7: Generativity versus Stagnation

As people reach middle adulthood, they strive to become productive members of society, contributing to future generations through parenting, meaningful work, or community involvement. If they fail to achieve this, they may experience stagnation, marked by feelings of unproductiveness or a lack of purpose.

Stage 8: Integrity versus Despair

In old age, people examine their lives. They may either have a sense of contentment or be disappointed about their lives and fearful of the future.

Erikson’s theory is useful because it addresses both personality stability and personality change. To some degree, personality is stable because childhood experiences influence people, even as adults. However, personality also changes and develops over the lifespan as people face new challenges. The problem with Erikson’s theory, as with many stage theories of development, is that he describes only a typical pattern. The theory doesn’t acknowledge the many differences among individuals.

Adverse Childhood Experiences

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) refers to potentially traumatic events or challenging circumstances that occur during childhood, such as abuse, neglect, household dysfunction, or exposure to violence. Research has shown that experiencing ACEs can significantly affect physical, emotional, and social development, often influencing the relationships individuals form throughout their lifespan. The impacts of ACEs can lead to difficulties in establishing trust, managing emotions, and maintaining stable, healthy relationships in adulthood. People with a history of ACEs may experience heightened sensitivity to stress, a tendency toward avoidance in relationships, or challenges in emotional regulation, often as a result of early attachments disrupted by adverse conditions.

ACEs have also been linked to insecure attachment styles, such as anxious or avoidant attachment, which may affect how individuals connect with others and handle intimacy, trust, and conflict. For example, individuals with insecure attachment stemming from early adverse experiences may struggle to feel safe in relationships or may exhibit patterns of dependency or detachment. These difficulties are often a response to past traumas and can affect interpersonal relationships across the lifespan, impacting friendships, romantic relationships, and even workplace dynamics.

Cultural and societal factors influence what is considered an ACE and how these experiences affect individuals. Different societies and cultural groups may have varying norms and values regarding adversity, resilience, and support systems, which can shape both the experiences themselves and the outcomes. For instance, what one culture perceives as adverse (such as strict parental discipline) might be viewed as normative in another. Additionally, access to mental health resources, community support, and family structures vary across cultures, impacting how individuals process and recover from adverse experiences.

In some communities, strong social networks, extended family support, or communal coping mechanisms may mitigate the effects of ACEs, helping individuals build resilience and develop adaptive coping strategies. Conversely, in societies where mental health resources are limited or stigmatized, individuals face greater challenges in managing the impacts of ACEs.

Adolescent Identity Development

During adolescence, individuals undergo a critical period of identity formation, exploring and shaping a sense of self that will guide them into adulthood. Self-concept and self-image are closely linked to identity formation. Self-concept is the broader, more stable understanding of oneself, including beliefs about personal abilities, values, and personality traits. This develops gradually from childhood through adulthood. In contrast, self-image refers to the immediate perception of oneself, often shaped by appearance, abilities, and feedback from others. Adolescents’ self-image can be more changeable, as it may fluctuate based on social interactions and external evaluations. Together, self-image and self-concept play crucial roles in forming an adolescent’s overall sense of identity.

The process of identity development encompasses multiple facets of identity, such as racial and ethnic identity, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious beliefs, occupational aspirations, and family roles. During adolescence, thinking about possible selves – beliefs and ideas about who one may become, would like to become, and is afraid of becoming – allows individuals to explore different facets of identity without fully committing to them. Possible selves also serve a practical function in that they motivate behavior and guide decision-making toward the goal of improving oneself, making predictions about future possibilities, and avoiding feared versions of oneself. For example, an adolescent who envisions a “possible self” as a physician might work hard academically, join science clubs, or volunteer at a hospital. The possible selves are part of a person’s self-concept and are critical in the process of identity formation. They help adolescents experiment with and eventually commit to a coherent sense of self.

James Marcia’s Identity Theory

Psychologist James Marcia expanded on Erik Erikson’s theories of identity by identifying four primary identity statuses that adolescents typically experience on their way to identity achievement: achievement, diffusion, foreclosure, and moratorium. These identity statuses are defined by the degree of exploration and commitment present. Exploration refers to the process of actively questioning, investigating, and experimenting with different roles, values, beliefs, and career options. During exploration, adolescents try out various identities, reflect on their personal interests and values, and assess potential futures. Commitment is the decision to adhere to a set of roles, values, or goals after a period of exploration. It involves making choices about who one is and wants to become, solidifying a direction that provides stability and a sense of purpose.

Diffusion: In identity diffusion, adolescents show little interest in exploring identity options or committing to any particular beliefs or goals. This lack of direction can result in a weak sense of self, often leading to feelings of confusion or apathy about the future. Adolescents in this status may feel disconnected from personal goals and uncertain about their place in the world.

Foreclosure: Adolescents in foreclosure commit to an identity without exploring other options, often adopting roles and values based on expectations set by authority figures, such as parents or cultural norms. While foreclosure may provide a temporary sense of security, it can limit personal growth and lead to an identity that feels externally imposed rather than personally meaningful.

Moratorium: The moratorium status is characterized by active exploration without commitment. Adolescents in moratorium are in the process of examining different roles, beliefs, and possibilities but have yet to settle on a particular identity. This period of exploration is often marked by questioning, self-reflection, and experimenting with various paths, which can lead to eventual identity achievement but may also come with uncertainty and anxiety.

Achievement: Identity achievement represents the culmination of exploration and commitment. Adolescents who reach this status have actively explored their beliefs and goals and have committed to a well-defined sense of self. They possess a strong understanding of their values, roles, and future goals and tend to experience high levels of self-esteem and stability.