The behavioral perspective in psychology is based on the idea that behavior is learned through interactions with the environment. This school of thought evolved from learning theories, namely, theories involving the concept of conditioning. Originating from the work of researchers like John B. Watson (also known as the “father of behaviorism”) and B. F. Skinner (known for introducing operant conditioning), behaviorism emphasizes that behavior can be studied scientifically by focusing on observable actions rather than internal mental states.

The behavioral perspective focuses mainly on behaviors as learned and modified through conditioning, a process in which associations are formed between stimuli and responses. There are two main types of conditioning: classical conditioning and operant conditioning.

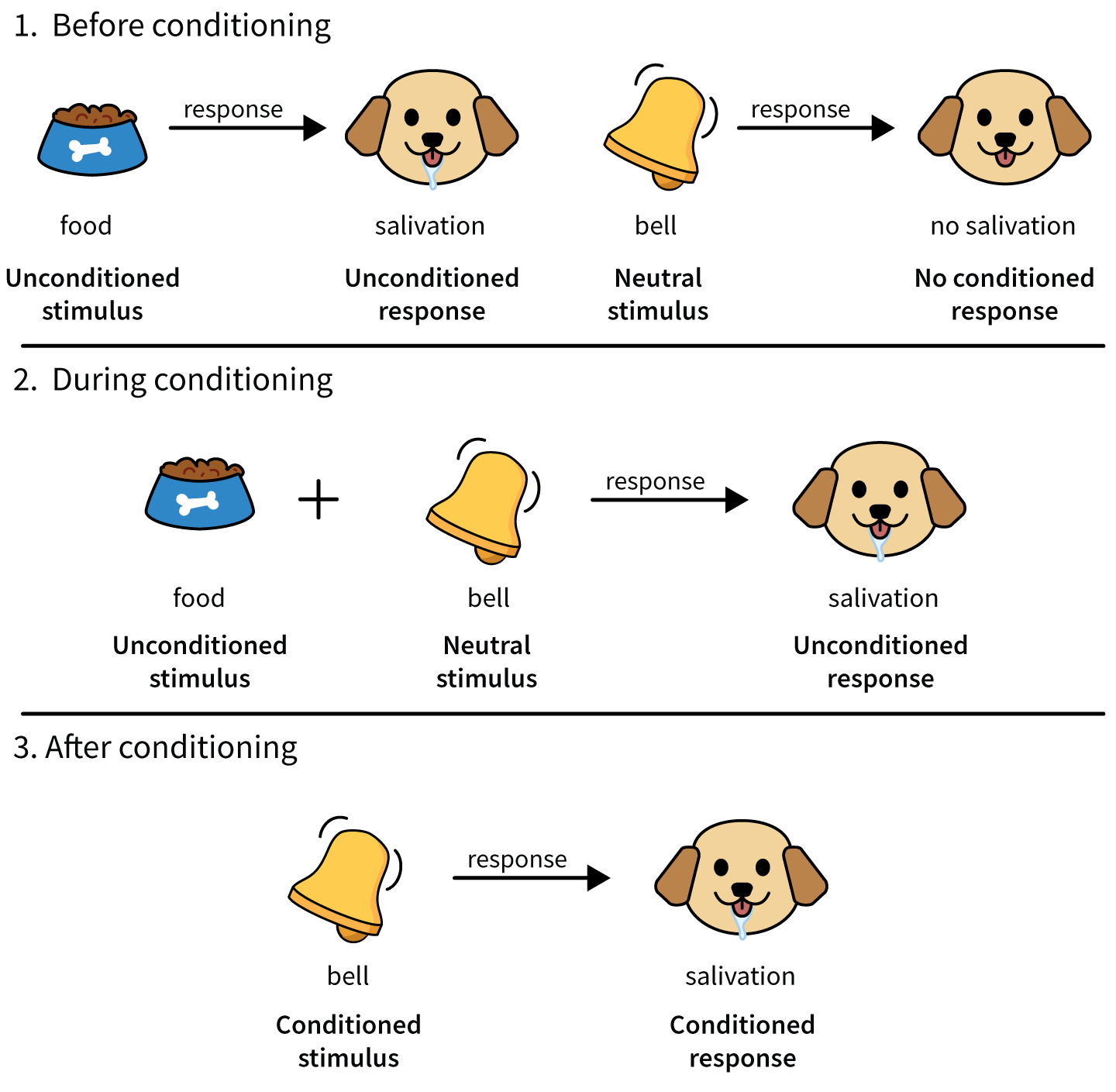

Developed by Ivan Pavlov, classical conditioning involves learning through association. In Pavlov’s most well-known experiment, dogs learned to associate a neutral stimulus (a bell) with an unconditioned stimulus (food) that naturally produced a response (salivation). Over time, the dogs began to salivate (the conditioned response) at the sound of the bell alone (the conditioned stimulus), demonstrating that the dog had learned a new behavior based on the learned association between the bell (the neutral stimulus) and food (the unconditioned stimulus).

Here are the key terms explained more fully:

Neutral Stimulus (NS): A stimulus that initially produces no specific response other than focusing attention. It becomes the conditioned stimulus once it’s associated with the unconditioned stimulus. In Pavlov’s experiment, the sound of the bell was initially a neutral stimulus because it didn’t cause the dogs to salivate before conditioning. But once conditioned, the bell became the conditioned stimulus.

Unconditioned Stimulus (US): A stimulus that naturally and automatically triggers a response without any prior learning. In Pavlov’s experiment, the food presented to the dogs was the unconditioned stimulus, because it naturally caused salivation.

Unconditioned Response (UR): The unlearned, naturally occurring response to the unconditioned stimulus. In Pavlov’s experiment, the dogs’ salivation in response to food was the unconditioned response, because it is a response that occurs naturally without prior learning or associations.

Conditioned Stimulus (CS): The previously neutral stimulus that begins to trigger a conditioned response after being associated with the unconditioned stimulus. In Pavlov’s experiment, the bell sound, which started as the neutral stimulus, became the conditioned stimulus after being paired with food repeatedly and then causing salivation when presented alone.

Conditioned Response (CR): The learned response to the previously neutral stimulus, now the conditioned stimulus. In Pavlov’s experiment, the dogs learned to salivate at the sound of the bell alone. Salivation, which was initially a natural or unconditioned response, therefore became a conditioned response to the bell, a once neutral stimulus, but now a conditioned stimulus.

Acquisition

Acquisition refers to the process by which a neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus capable of eliciting a conditioned response. Acquisition is the initial stage in classical conditioning, during which the organism learns the association between the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus. The association strengthens through repeated pairings of the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus, and the neutral stimulus gradually elicits a response on its own.

Factors such as the frequency of pairings, the timing between the neutral and unconditioned stimuli, and the order of presentation can influence the speed and strength of acquisition.

Order of Presentation

The order of presentation of the neutral stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus is critical for effective learning. In classical conditioning, the neutral stimulus should come before the unconditioned stimulus for the learned association to be effective. For instance, the bell should ring shortly before the food is presented rather than the other way around. This arrangement, known as forward conditioning, is generally more effective than backward conditioning, in which the unconditioned stimulus (the food) is presented before the neutral stimulus (the bell).

Extinction and Spontaneous Recovery

Once a conditioned response has been established, it can diminish if the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus. This process is called extinction. For example, if Pavlov rang the bell without introducing food, the dogs’ salivation response to the bell would gradually weaken and eventually disappear. However, even after the conditioned response is extinguished, it may reappear unexpectedly in a phenomenon known as spontaneous recovery. If the conditioned stimulus (the bell) and the unconditioned stimulus (the food) are paired again after extinction, the conditioned response (salivation) can return, albeit often weaker than before. This recovery suggests that extinction does not entirely erase the learned association but suppresses it.

Stimulus Generalization and Discrimination

Two additional principles of classical conditioning are stimulus generalization and stimulus discrimination. Stimulus generalization occurs when stimuli similar to the original conditioned stimulus elicit the conditioned response. For example, a dog conditioned to salivate at the sound of a bell may also salivate in response to other similar sounds, such as a chime or buzzer. Generalization allows organisms to respond to new but similar stimuli, enhancing adaptability.

Stimulus discrimination is the ability to distinguish between the conditioned stimulus and other stimuli that do not signal the unconditioned stimulus. Using Pavlov’s experiment as an example, the dog would learn to discriminate by learning to salivate only after a specific bell tone and not after other bell-like sounds. This skill helps organisms fine-tune their responses to particular cues, avoiding unnecessary reactions to irrelevant stimuli.

Higher-Order Conditioning

In classical conditioning, once a conditioned response has successfully elicited a conditioned response, it can sometimes be used as an unconditioned stimulus in a process called higher-order conditioning (also known as second-order conditioning). This means that an additional neutral stimulus can become associated with the conditioned stimulus already established, forming a new conditioned stimulus that elicits the same conditioned response.

In the case of Pavlov’s dog, the dog has been conditioned to salivate at the sound of a bell (the conditioned stimulus) because the bell was paired with food (the unconditioned stimulus), which naturally caused salivation (the unconditioned response). If a new neutral stimulus is introduced, such as a light, and is consistently presented just before the bell rings (without any food), the dog may eventually learn to associate the light with the bell. Over time, the light alone may elicit the conditioned response of salivation, even though it was never directly paired with the food. In this case, the bell has become the unconditioned stimulus for the light, and the light has become a new conditioned stimulus through higher-order conditioning. This process demonstrates that conditioned responses can be expanded through additional layers of association, though responses tend to be weaker with each additional level of conditioning.

Classical Conditioning and Emotional Responses

Research has shown that emotional responses can be conditioned through classical conditioning, leading individuals to associate particular emotions with specific stimuli. These emotional associations are particularly significant because they often form involuntarily and can persist over time, influencing how individuals react to certain situations or cues in their environment. This understanding of conditioned emotional responses has become a foundation for therapeutic interventions aimed at addressing mental health challenges.

A classic example of conditioned emotional responses comes from John B. Watson’s well-known “Little Albert” experiment, where a young child was conditioned to fear a white rat by pairing it with a loud noise. Over repeated pairings, Little Albert began to experience fear at the sight of the rat alone, even without the noise. This demonstrated how neutral stimuli can become associated with strong emotional reactions, such as fear or anxiety, through conditioning.

The principles of classical conditioning, particularly as they relate to emotional responses, have led to therapeutic techniques that help individuals unlearn undesirable associations, including systematic desensitization, exposure therapy, and flooding.

Taste Aversion

Psychologist John Garcia and his colleagues found that aversion to a particular taste is conditioned only by pairing the taste (a neutral stimulus) with a negative experience, like nausea (an unconditioned stimulus), which feels bad (an unconditioned response). If taste is paired with other unconditioned stimuli, like a pleasant conversation during the meal, conditioning doesn’t occur.

Similarly, nausea paired with most other conditioned stimuli (like sounds, visual stimuli, or social contexts) doesn’t produce aversion to those stimuli. Pairing taste and nausea, on the other hand, produces conditioning very quickly, even with a delay of several hours between the conditioned stimulus of the taste and the unconditioned stimulus of nausea. This phenomenon is unusual since, normally, classical conditioning occurs only when the unconditioned stimulus immediately follows the conditioned stimulus. In this kind of fast learning, known as one-trial conditioning, an association between a particular taste and an unpleasant response, like nausea, can be established with just one exposure. This phenomenon was demonstrated by psychologist John Garcia in experiments where he conditioned rats to avoid a specific taste by pairing it with sickness. Even after just one pairing, the rats avoided the taste in future encounters, demonstrating that taste aversions don’t require repeated pairings, as is the case with typical examples of classical conditioning.

Example: Jamie eats pepperoni pizza while watching a movie with his roommate, and three hours later, he becomes nauseated. He may develop an aversion to pepperoni pizza, but he won’t develop an aversion to the movie he was watching or to his roommate, even though they were also present at the same time as the pizza. Jamie’s roommate and the movie won’t become conditioned stimuli, but the pizza will. If, right after eating the pizza, Jamie gets a sharp pain in his elbow instead of nausea, it’s unlikely that he will develop an aversion to pizza as a result. Unlike nausea, the pain won’t act as an unconditioned stimulus.

The concept of biological preparedness, proposed by Martin Seligman, helps explain why taste aversions are acquired so efficiently. Biological preparedness suggests that animals, including humans, are biologically predisposed to learn certain associations more easily than others due to evolutionary adaptations. In the case of taste aversions, organisms are naturally inclined to associate food with illness, as this ability has likely evolved to protect against consuming toxic substances. This predisposition helps explain why taste aversions are particularly strong and long-lasting, while associations between other types of stimuli (such as sounds or lights) and nausea are less-readily learned. Humans, and other animals, are biologically wired to learn and maintain associations that will help them survive and avoid harm.

Habituation

Habituation is a simple form of learning in which an individual gradually becomes less responsive to a repeated or prolonged stimulus. Over time, the individual’s response to the stimulus weakens as he or she become desensitized to it, leading to a diminished reaction. Habituation makes it possible to conserve energy and attention by ignoring non-threatening or unimportant stimuli that recur frequently in one’s environment. The adaptive value of habituation is that individuals are better able to focus on novel or significant stimuli in their environments rather than being constantly distracted by familiar, repetitive sounds, sights, or sensations.

Example: Jaida moves to a new home near train tracks. She initially finds the occasional sound of a passing train to be distracting and somewhat irritating. However, after several days or weeks, she finds that she can’t remember the last time she heard the train go by. She realizes that her brain has habituated to the noise of the train such that she no longer registers it.

Habituation can occur in various settings and across different species. Infants, for instance, show habituation when they stop paying attention to a toy they have seen many times, preferring instead to focus on new or unfamiliar objects. In animals, habituation is also observed in response to repeated exposure to harmless stimuli, like a cat ignoring the sound of a doorbell after realizing it doesn’t signal anything significant.

While habituation is generally beneficial, it can also be temporary. If the repeated stimulus suddenly stops and reappears after a while, the response may briefly increase again before diminishing once more. This re-emergence of the response is known as spontaneous recovery.