Monopolies are the best-known type of imperfect market, but not the only type. Three other types are worth covering briefly.

Monopolistic Competition

A market structure with many sellers and fairly easy market entry and exit, but with limited substitutability of products, is called monopolistic competition. The limited substitutability of the products is deliberate, a result of product differentiation. Products may deliberately be configured to have unique compatibility requirements (think Apple vs. other personal electronic devices). Advertising may be used to emphasize the features that make one product different from others.

In the short run, the analysis of firm’s profit in such a market looks much like the analysis for a monopolist. Thus firms in monopolistic competition may earn significant profits. In the long run, however, those profits will attract other firms, because market entry is easy. The drop in demand for each individual firm’s output will erode profits until each firm’s profit equals zero, just as in a competitive market.

Oligopolies

In an oligopoly market, there are just a few sellers, and market entry and exit are fairly difficult. None of the firms faces the entire market demand curve in the way a monopolist would, but each is large enough to affect prices by its output decisions.

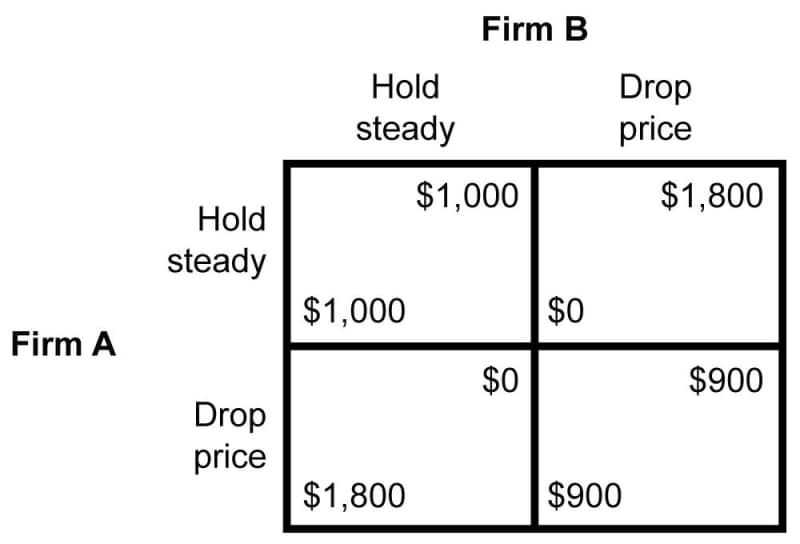

In principle, even in a duopoly market, where there are just two sellers, competition should drive prices down to the point where neither firm is earning a profit. After all, if the market allows both firms to make a profit at price p, one firm ought to be able to capture the entire market and nearly—but not quite—double its revenues by dropping its price just a bit below p. But the other firm will drop its price, too, to keep that from happening. We can picture the dynamic as a two-player game in which each player chooses “Hold steady” or “Drop price,” resulting in payoffs shown below as sample revenues. In each cell, Firm A’s revenue is on the lower left and Firm B’s is on the upper right.

Whatever Firm A does, Firm B is better off choosing “Drop price,” and whatever Firm B does, Firm A is better off choosing “Drop price”—even though both firms end up worse off than if they had both chosen “Hold steady.” This game is an example of a prisoner’s dilemma. (An early description of this kind of game involved two prisoners.) “Drop price” is the dominant strategy. In an ideal duopoly, the game will repeat and keep pulling prices downward until there are no more profits to be captured. The same kind of thing happens in a market with more than two firms. In fact, the prisoner’s dilemma is a convenient way of picturing the price-lowering effect of free-market competition.

In practice, firms in an oligopoly will look for ways to differentiate their products from one another, so that one firm’s output is a less-than-perfect substitute for another’s. This makes it easier for the firms to avoid the prisoner’s dilemma dynamic that drags their prices downward. Also, firms in an oligopoly may engage in collusion, quietly agreeing among themselves to keep prices high. Such behavior is generally a violation of antitrust laws and can cause firms to be subject to legal prosecution.

Monopsonies

A monopsony is the flip side of a monopoly, a market where there are many sellers but just one buyer. Monopsony markets in goods and services are uncommon, but for a simple example, imagine a region where many small coffee growers sell raw beans to a single buyer that roasts the beans for sale to consumers or resale to an exporter. The market in raw beans, where the farmers are the sellers, is a monopsony market.

Monopsonies are more common in labor markets, where households are the sellers and firms are the buyers. Think of a “company town” where a single firm—the local auto plant, for instance—is the dominant employer.