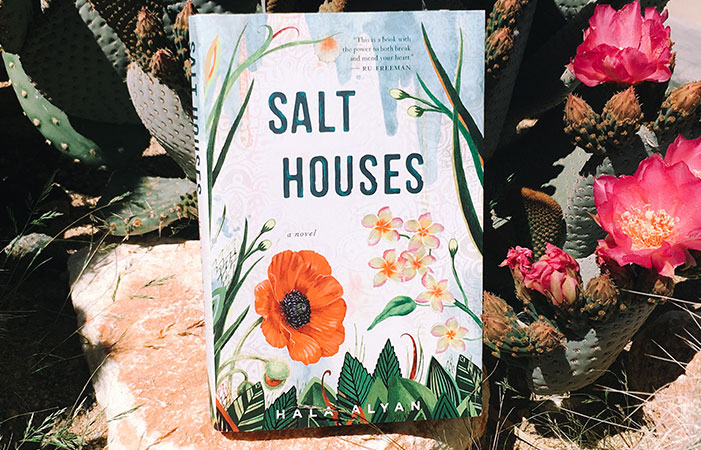

Salt Houses Author Hala Alyan on Finding a Home, Airport Detention, and The Role of Art in Talking About Palestine

Picture your childhood home.

Your parents might still live there. A new family might have moved in. It might exist only in the background of family photos. What does it mean when you can’t go back to that house?

Debut novelist Hala Alyan has taken the notion that “You can never go home again,” and turned it into an epic story about a Palestinian family displaced by war and scattered around the globe. The matriarch, Salma, sees turmoil in the tea leaves the night before her daughter Alia’s wedding, back when Alia doesn’t want to move away to get married, and it is still unfathomable that the family would leave Nablus, Palestine. The Six-Day War of 1967 flings Alia, her sister Widad, and her brother Mustafa along different paths, and the family’s expulsion from Palestine manifests in different ways in Alia’s children, who find their way to Paris, to Boston, to Jordan, and live through the 1990 invasion of Kuwait when the family is uprooted again. Watching the next generation grapple for a place in the world, you will get lost thinking about the ways that our ideas about love, home, and trauma are handed down.

A coping technique—for coping with being yourself, I guess—is to see yourself as part of a bigger picture, a bigger system, and Hala Alyan’s ability to build this shimmering, bright, disappeared world for the Yacoub family, and to find a way to for the characters to reach back and touch it, will give you hope. The complex and often funny dynamics between various sisters and brothers will remind you how important your own siblings are to you, even though they drive you full-time bananas.

Along with being an accomplished poet and performer, Hala Alyan is a clinical psychologist and whip-smart conversationalist. We were lucky enough to talk with her about the tricky road to Palestine, where we get our ideas about love, and airport detention (ha).

Salt Houses is ~incredible~, and out May 2! You can pre-order it here.

SparkNotes: We talk a lot about what we call “world building” in sci-fi-fantasy, but I feel like we could apply the term to what you’ve done in Salt Houses with Nablus. How did you go about constructing Salma’s home?

Hala Alyan: It started out as a short story of what is now the Mustafa chapter, and when I started falling in love with and getting fascinated by the mother and the sister, the idea of that house started to feel a lot more important and I really wanted some sort of visual guide to go of off.

So what I did at the time was Google and ask my friends for as many photos of Palestine in the ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s as they could find, to get a sense of what the streets looked like, what the market places looked like. I have been to Nablus, obviously, in real life, and it’s the kind of place that hasn’t changed radically, like there are a lot of new stores and restaurants, but the structure and the architecture is one such that I could walk through it and feel a little bit transported, especially through the market place, to 50 years ago. So I kind of started with that, with visual aides, being there trying to pay attention to what it smelled like, to what the temperature was like to try to have these details be as authentic as possible, and the rest of it was just making things up. (Laughs)

You are interested in the way a place can bring things out in a person. What does the difficulty of actually traveling to, and getting into, the Palestinian territories change about those places, or your experience going there?

Oh you mean literally. I like that. So I think it does impact it, right? When I’ve gone to Palestine I’ve gone through the airport, I’ve never driven in through Jordan, although I’ve heard people say that’s easier. It just depends on who you’re going to get at the border, who you’re going to get at the airport, what kind of day they’ve had, I think a lot of factors go into play. I know people who have gotten in without a problem, and people who have been detained and actually sent back, not allowed to come in. But the experience of a lot of people who I’ve spoken to about it is one where you get the sense that in some ways there might be an effort to make it as difficult as possible, where you do get those vibes at the beginning of, “Oh, I don’t know if I’m supposed to be here, I don’t know if I’m wanted here.”

And going through checkpoints to get into the West Bank it feels like a bit of a cheat to be able to flash the blue passport, so I do think the intersection of space and person was very salient there because I felt very American in a way I didn’t expect to. I realized I had so much privilege because of the passport that I carried, and that I can speak English without an accent, and I live in New York. But I particularly like that question because by the time you get to the literal land you’ve already been given all of these environmental cues that you’re not supposed to be here and that this isn’t yours, and so the relationship with Palestine, with the actual place physically, ends up being this really multilayered, complicated one where there’s a piece of diasporic tourism, but I’m also just really here to see what it’s like, and people here are living their lives, and what does that mean. And the amount of kindness and generosity shown to me by so people while I was there made me feel more so like I was a guest.

I really like that line about Manar’s Palestinian identity being a hat rack for whatever she feels psychically is missing. The book makes a really good case finding a way to preserve the past, to capture your memories, what else has your clinical background taught you about homesickness and dealing with displacement?

Well it’s trauma, right? I mean I strongly believe in intergenerational trauma. You see it in research with Holocaust survivors and the descendants that follow them. At some point in the family lineage if a place was lost that is a very vivid trauma that then gets lived and passed down and inherited in different ways by the generations that follow. And I think it can result in all sorts of restlessness, sadness, malaise, anxiety. I think one of the things that I definitely see in my generation in my family is this anxiety and this constant expectation. Like my brother has this running “joke” that whenever one of us calls the other person and we don’t immediately sound chipper, the other is like, “What’s wrong?” And that’s not normal, but it’s what we’ve seen from our parents.

I was four during the (Kuwait) invasion, so I saw it very briefly, but I’m sure it’s coded there somewhere that the next catastrophe might be waiting around the corner, so that’s something I see in my generation of family members, people who might have been born in the Middle East, or even here—this feeling of you can’t get too comfortable because you don’t know when you’ll have to leave.

What do you mean when you talk about the Palestinian diaspora? Is it a straightforward term?

I’ll tell you how I’ve heard of it and how I’ve heard it defined. I think of it as people who are of Palestinian descent and for one reason or another had to leave—that might have been in ’48, or ’67, that might have been pre-’48—and who live in places other than Palestine. So there are members of the diaspora in New Zealand, in Brazil, in New York, and it sort of ends up being this scattered identity that becomes its own identity, becomes its own community.

In the U.S. it can be difficult for people to have a conversation around Israel and Palestine, and I wonder whether you think art and literature are actually one of the better avenues to open up space to discuss it.

It’s an identity that even of itself can cause certain people to bristle, right? It’s an identity that’s up for debate in some circles to even say, “I’m Palestinian-American.” So when you’re starting with that, especially in certain places in the West—and I definitely think the United States is one of those places—then kind of everything that happens after that is going to be considered by some as political. And in writing this I didn’t want to pretend that there wasn’t a political context for all of this—like this family becomes displaced because of political turmoil and war, and there is no way to avoid that. There is no way to tell a multigenerational story about a Palestinian family and avoid that.

But there is some value to art and about story telling that allows for different narratives than some readers might be used to, that might be a little bit more digestible. So for some people instead of breaking a window, it’s like knocking on the door and saying, “let me in, let me tell you this story about a family.” And afterward, they can think about, Well, this is a Palestinian family, and how does this speak to the narrative as I understand it?

So I do think art, and even comedy and music, can be extremely powerful vehicles for offering alternatives to mainstream narratives in a way that people oftentimes are less guarded against than just a straight political debate.

You have talked about trying to counter the exoticised portrayals of the Arab world we often get, and writing a multifaceted book with multiple generations achieves that, so I wonder if the different ways the characters experience love plays into that, or not at all?

Totally, I mean you learn how to love based on the blueprints you’ve been given, and those blueprints change if your parents courtship happened in transit, for example. Or if you grew up watching a marriage take place in a country that wasn’t their own. Those things impact how we think of love, of relationships, how we also frankly think about stability. If you’re always waiting for the next catastrophe, if you’ve gotten used to living in that metaphorical borderland, then that definitely impacts how we search for love. And it definitely comes up with the characters. One straight-up gets married to avoid having to move to a country she doesn’t want to go to, and those are things that actually take place.

So the things that we end up seeking in each other, and how it becomes that much more important to have other people become a sort of home for you, if you don’t have that, the stakes become higher when it comes to family, and partners, and children, it changes that entire landscape.

I read that you managed to do some writing while in the detention area of the Tel Aviv airport. What did you write?

Oh my god that’s so funny. Well, first I wrote the names of everyone in my family because they asked for that (laughs), but I was writing a little note to myself to try to remember the amount of privilege that I have that I know that whatever happens in this situation I’ll be okay. That even if I’m detained for a little bit and end up having to go back to the States—like in my case I waited for a few hours but it was relatively smooth—it was just time. So I ended up writing a scene that I knew would be incorporated later on, that ended up being used in the Manar scene, of what it would be like for a character to be sitting and waiting and waiting and not knowing what would come next.

I was also a bit younger. I do feel like I’m a lot more skittish now, but there was a bit of that youthful invincibility, so I might be a lot more of a wreck now.

This interview has been edited and condensed.