To Understand Much Ado About Nothing, Watch When Harry Met Sally

What’s the difference between a Shakespearean comedy and a tragedy? In one everyone gets married at the end, in the other, everyone dies. I mean, there are some qualifications regarding fatal, ironic character flaws, but basically it comes down to whether the story ends with the mournful “When Doves Cry” or the jubilant “Everybody Loves Somebody” and a bunch of pashing.

What’s the difference between a Shakespearean comedy and a tragedy? In one everyone gets married at the end, in the other, everyone dies. I mean, there are some qualifications regarding fatal, ironic character flaws, but basically it comes down to whether the story ends with the mournful “When Doves Cry” or the jubilant “Everybody Loves Somebody” and a bunch of pashing.

If you’re boots-deep in a Shakespearean comedy right now, and struggling to find Greater Meaning in the mardi gras of cross-dressing, mistaken identity, and bum jokes, turn your attentions to the rom-com classic, When Harry Met Sally. It’s Much Ado About Nothing plus ’80s hair, _what_ _is_ _not_ _to_ _like?

Much Ado About What Exactly?

Much Ado follows two ascendent couples: the “heroes,” or romantic leads, Claudio and Hero, who provide the B-storyline, and the comic heavies and anchors of the A storyline, Benedick and Beatrice.

(Style note: I tried out for the witty Beatrice in my high school production, but was instead forced to don a beard and play Claudio, if you’re wondering where I fell on the hot-girl totem pole during my teens.)

Dramatic momentum comes from waiting for these two couples to get. it. on. through the play, as various obstacles keep them apart. Being Shakespeare, these obstacles are exquisite.* The B storyline: a maid impersonating Hero appears in a window before Claudio, making out with another guy, and thus ruining her “virtue.” The only way for her to recover her reputation is to pretend to have died, then be introduced at the end as her own cousin. (Wasn’t that the plot of an episode of The Bachelor?) The A storyline: Benedick and Beatrice are each so stubborn, sarcastic, caustic, and good at hiding their true feelings that neither is capable of admitting they like the other until they are tricked into doing so. *There is a villain, Don Pedro (who was played by Keanu Reeves in the ’90s film adaptation(!)), but he’s about as complex as a cardboard cutout of Cedric Diggory.

Congratulations, me—this is the shortest Shakespearean plot summary you will ever find. 🔑🔑🔑

“Sex Always Gets in the Way”

To make sense of the above plot movements, let’s now leave our pantaloons in Tuscany (Messina) and journey back to the center of the world, New York City, where we find college grads Harry and Sally driving into town to begin their adult lives, Sally believing Harry to be a beeet of a ladies man and Harry believing her to be a leedle bit of a prude, and possibly too good for him.

At this stage, we are a dozen years and ten Meg Ryan hairstyles away from these two getting together.

Nora Ephron’s leads are mashups of Benedick/Beatrice and Claudio/Hero, hamstrung by their own preconceptions about love and the opposite sex:

HARRY BURNS: There are two kinds of women: high maintenance and low maintenance.

SALLY ALBRIGHT: Which one am I?

HARRY BURNS: You’re the worst kind; you’re high maintenance but you think you’re low maintenance.

Shakespeare’s difficult leads are just as prejudiced, even if Beatrice believes herself more immune to romance than the idealistic Hero and Sally, performing several variations on “MEN. Can’t live with them, can’t get to a denouement without them”:

BEATRICE: He that hath a beard is more than a youth, and he

that hath no beard is less than a man; and he that is

more than a youth is not for me, and he that is less

than a man, I am not for him.

Benedick is just generally anti marriage (ew):

BENEDICK: A man loves the

meat in his youth that he cannot endure in his age.

The first conversation Harry and Sally have, in the car on the way to New York, is about how Harry believes men and women can never be friends, because “sex always gets in the way.” Harry means s.e.x., but of course we can read it at a slightly higher level to imply that men and women are incompatible—opposites that attract and repel. And, yas indeed, Harry and Sally end their first chapter on a misunderstanding of language, having arrived in New York City.

HARRY: Because no man can be friends with a woman that he finds attractive. He always wants to have sex with her.

SALLY: So, you’re saying that a man can be friends with a woman he finds unattractive?

HARRY: No. You pretty much want to nail ’em too.

SALLY: What if THEY don’t want to have sex with YOU?

HARRY: Doesn’t matter because the sex thing is already out there so the friendship is ultimately doomed and that is the end of the story.

SALLY: Well, I guess we’re not going to be friends then.

HARRY: I guess not.

SALLY: That’s too bad. You were the only person I knew in New York.

Gender is a barrier to their getting together, pitting them on opposite sides of an ongoing war (there are two wars going on in Messina, also!), and obscuring their honest feelings. In Much Ado, Claudio believes Hero has cheated on him, a symptom of the men’s inherent suspicion of women; in When Harry Met Sally, the famous Carnegie Deli scene demonstrates the powers of deception one sex is capable of, or, to flip it, the depth of male anxiety over their own sexual power.

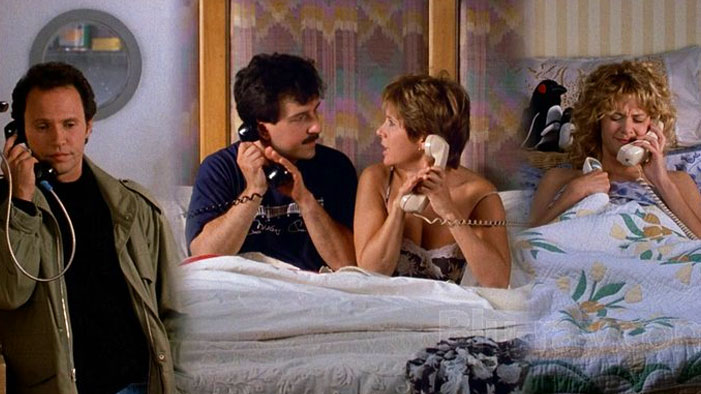

In both stories, girls align with girls (think of the scene in WHMS at Tavern on the Green where Marie offers her rolodex of guys to Sally, or Hero and Margaret plotting to out Beatrice’s feelings to Benedick), and boys align with boys. The characters find it endlessly difficult to admit their true feelings, with Marie only admitting to Jess that she has lived with and despised his “Roy Rogers” coffee table after Harry blows up and makes fun of it (“I will never… want that wagon wheel coffee table.“).

LEONATO: There is a kind of merry war betwixt Signior Benedick and [Beatrice]; they never meet but there’s a skirmish of wit between them.

The Sickness

In Shakespeare, as in life, love is a plague. After Hero is smeared as a slut (“she is fallen into a pit of ink”), she is “laid low” so she can be reborn as a virgin, ~basically~, while for Benedick, the realization that he loves Beatrice comes as happily as a terminal diagnosis (“Well, every one can master a grief but he that has it.”), and Beatrice jokes that she “suffers” love, because she is in love against her will.

For Harry and Sally, each takes turns helping the other through the sickness of heartache with other partners, wondering by turns whether they are sick from the person or from the condition of love itself, but never considering whether their sickness is actually unrequited love for each other:

HARRY: I miss her.

SALLY: I don’t miss him. I really don’t.

HARRY: Not even a little?

SALLY: You know what I miss? I miss the *idea* of him.

HARRY: Maybe I only miss the *idea* of Helen… No, I miss the whole Helen.

Elsewhere, Harry jokes about the fact that lovesickness can take a human form:

JESS: Marriages don’t break up on account of infidelity. It’s just a symptom that something else is wrong.

HARRY: Oh really? Well, that “symptom” is f* ¢king my wife.

It’s the kind of joke Billy Shakespeare (sorry) would have enjoyed, having devoted so many lines to the idea that love is temporary insanity (“for man is a giddy thing”).

Here they are helping each other through another tormented breakup with someone else. WHY CAN’T THEY SEE THEY LOVE EACH OTHER??

In another sense, Harry is right that s-e-x gets in the way: after he and Sally finally do it, a new divide opens up between them, with Harry not saying the words Sally needs to hear (“ily,” for the obtuse menfolk out there), and Sally feeling like she has given up the ghost without getting the all-important “ily” in return, and that things have, as a result, changed forever (as retro as that sounds). For this reason, it’s important that Beatrice and Benedick are held to their word with two letters stating their affections on hand at the moment of truth in Act 5 Scene IV.

The Masks We Wear

As I say^, Meg Ryan’s various perms through the years are a ~treasure~ in WHMS, but they also function like the [real and metaphorical] masks that Shakespeare’s characters wear throughout his plays. The deceptions and confusions that keep the romantic leads apart all come down to the gap between reality and representation, between how people act and how they feel, between the things they say and they things they mean.

The characters themselves struggle with how to interpret the words of their paramours. Here is Benedick trying to guess the hidden meaning (there isn’t one) in Beatrice’s fetching him to dinner:

BENEDICK: Ha! ‘Against my will I am sent to bid you

come in to dinner.’ There’s a double meaning in

that. ‘I took no more pains for those thanks than

you took pains to thank me.’ That’s as much as to

say ‘Any pains that I take for you is as easy as

thanks.’ If I do not take pity of her, I am a villain; if I

do not love her, I am a Jew. I will go get her picture.

And here’s Harry leaving a soliloquy/message on Sally’s phone machine after he says something dumb (they hooked upppp!):

HARRY: The fact that you’re not answering leads me to believe you’re either (a) not at home, (b) home but don’t want to talk to me, or (c) home, desperately want to talk to me, but trapped under something heavy. If it’s either (a) or (c), please call me back.

His inability to tell Sally he loves her and wants to be her after they finally make out becomes a new barrier. We need a verbal resolution—the great, romantic speech—as well as the kiss, to get a happy ending. Until then, more tortured rhetoric. In Messina:

BENEDICK: Do not you love me?

BEATRICE: Why no, no more than reason.

BENEDICK: Why then, your uncle and the Prince and Claudio

Have been deceived. They swore you did.

BEATRICE: Do not you love me?

BENEDICK: Troth, no, no more than reason.

Meanwhile in New York, an ironic inability to get beyond “friends.”

HARRY: Would you like to have dinner?… Just friends.

SALLY: I thought you didn’t believe men and women could be friends.

HARRY: When did I say that?

SALLY: On the ride to New York.

HARRY: No, no, no, I never said that… Yes, that’s right, they can’t be friends.

The Resolution

Having painted themselves into corners with their sundry protests that they *don’t* love the other person (any more than reason), Beatrice/Benedick and Harry/Sally have a hard time admitting that they *do.* Benedick tries to write a moving speech, but fails:

BENEDICK: Marry, I cannot show it in rhyme. I have tried. I can find out no rhyme to “lady” but “baby”—an innocent rhyme; for “scorn,” “horn”—a hard rhyme; for, “school,” “fool”—a babbling rhyme; very ominous endings. No, I was not born under a rhyming planet, nor I cannot woo in festival terms.

Harry has somewhat better luck putting his feelings into words:

HARRY: I love that you get cold when it’s 71 degrees out. I love that it takes you an hour and a half to order a sandwich. I love that you get a little crinkle above your nose when you’re looking at me like I’m nuts. I love that after I spend the day with you, I can still smell your perfume on my clothes. And I love that you are the last person I want to talk to before I go to sleep at night. And it’s not because I’m lonely, and it’s not because it’s New Year’s Eve. I came here tonight because when you realize you want to spend the rest of your life with somebody, you want the rest of your life to start as soon as possible.

Oh. My. God.

Neither Sally nor Beatrice can resist.

BEATRICE: I love you with so much of my heart that none is left to protest.

SALLY: You see? That is just like you, Harry. You say things like that, and you make it impossible for me to hate you.

That is, despite their character flaws (stubbornness, head-over-heart approach to life (“Though and I are too wise to woo peaceably.”)), they have been conquered by love. <3

So much ado (twelve years of messing around!) over nothing.

Other commonalities that are less relevant to your essays and only interesting if you have watched When Harry Met Sally forty times

- Both Benedick and Harry sing in their respective love stories.

- They’re all in their thirties when they finally succumb to the vapors and get hitched (so basically nothing has changed since the 16th century).

- Harry and Sally inadvertently set up their friends Marie (Princess Leia!) and Jess, when they go on a blind date as a foursome, and are ditched by their intended dates, which has the effect of setting up Harry + Sally down the line, just as Benedick and Beatrice are “set up” by Beatrice’s cousin, and Benedick’s manfriends.

Are you a sucker for rom-coms of the Shakespearean or Ephron in origin? Are you thrilled to have an excuse to watch Billy Crystal hug Meg Ryan for the 50th time “for school”?